Dancing while Rome Burns

Technically speaking, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are over. The last American forces pulled out of Iraq in 2011, and President Obama recently announced that

all U.S. troops will leave Afghanistan by the end of 2014

. But for many Americans, Iraqis and Afghans, the conflict lingers—whether in real terms (through suicide bombings and sectarian violence), in physical scars (there are

at least 1,500 major limb amputees

to date from both wars), or in psychological traumas that visit every time a car backfires or a firework goes off.

Technically speaking, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are over. The last American forces pulled out of Iraq in 2011, and President Obama recently announced that

all U.S. troops will leave Afghanistan by the end of 2014

. But for many Americans, Iraqis and Afghans, the conflict lingers—whether in real terms (through suicide bombings and sectarian violence), in physical scars (there are

at least 1,500 major limb amputees

to date from both wars), or in psychological traumas that visit every time a car backfires or a firework goes off.

Magnum photographer Peter van Agtmael is intimately acquainted with the real-life stories behind these facts. In 2006, as a twenty-four year old Yale graduate in History, he set off for Iraq to photograph the war there. Over the next six years, van Agtmael spent large amounts of time in both countries, often embedded with troops who were being sent on risky patrols of questionable value. Back in the U.S., as the wars dragged on, he noticed a growing weariness and disinterest in what was happening overseas, and this disconnect is the subject of his important new book, Disco Night Sept. 11 .

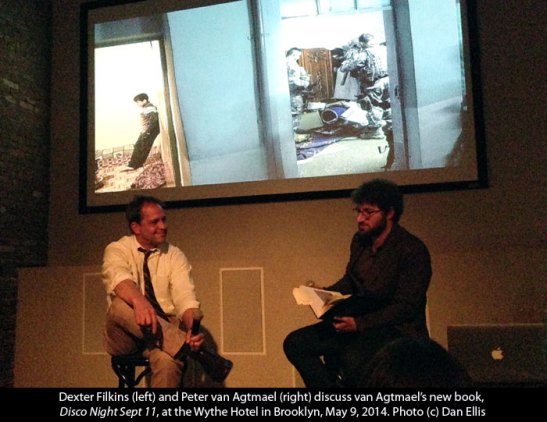

Last Friday, I went to the Wythe Hotel in Brooklyn to hear van Agtmael in conversation with Dexter Filkins , the Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times correspondent who is now a New Yorker staff writer. Filkins has covered the two wars extensively, and he and van Agtmael have been embedded together more than once. Filkins’ 2008 book The Forever War is “a classic,” van Agtmael told the audience.

It’s obviously a bit strange to discuss the brutalities of war when you’re sitting in a plush screening room in a boutique Brooklyn hotel, and perhaps because of this, the two men started off on a jokey note. “Boy, we should go on tour—this might be the funniest war presentation ever,” mused van Agtmael after he’d told an anecdote about Filkins’ boots melting in Afghanistan, and Filkins had remarked, “I’m just going to sit here and look pretty.”

But van Agtmael—who came across as extremely sincere and smart—turned serious when it came to discussing his reasons for creating the book (a follow-up to his first book, 2nd Tour Hope I don’t Die ). “One of the things that got me into this was just a belief in and love for journalism,” he said. He also owned up to having been fascinated by war ever since he could remember, and wanting to see what would happen if he brought the “intangible, indescribable” quality of photography to it.

Once in Iraq, van Agtmael soon found himself confronting highly nuanced situations. There were soldiers who—in an attempt to blunt their guilt and pain—likened their killings to Hollywood movies. There were night raids where random searches of residents occasionally turned up bomb-making equipment, but caused commotion and bred bitterness when they didn’t. “Your basic commanding officer is a decent, sincere guy who wants to do the right thing, but he’s out of his depth,” van Agtmael remarked.

Once in Iraq, van Agtmael soon found himself confronting highly nuanced situations. There were soldiers who—in an attempt to blunt their guilt and pain—likened their killings to Hollywood movies. There were night raids where random searches of residents occasionally turned up bomb-making equipment, but caused commotion and bred bitterness when they didn’t. “Your basic commanding officer is a decent, sincere guy who wants to do the right thing, but he’s out of his depth,” van Agtmael remarked.

He tried to express this complexity through several images, in one of which a terrified boy stands in a living room while, in the room next door, soldiers tear apart his family’s possessions. In another almost surreal image, a heavily armed soldier sits on duty in a yellow-on-yellow living room that could be somewhere in the American ‘burbs. In a third (image above), an angry-looking young soldier sits next to a sleeping Afghan elder. (“It’s usually the other way around—the Afghan looks angry and the soldier looks sleepy,” Filkins joked.)

Meanwhile, in trips back to the U.S., van Agtmael found himself confronting situations that were equally poignant and dissonant. He watched waitresses flirt with marines during New York’s Fleet Week, and saw commercials for commemorative coins made from silver recovered from Ground Zero. He befriended several amputees and was with one, Raymond Hubbard, in a New York bar when a woman playing a shoot-em-up video game noticed his prosthesis and aimed her gun at him. “I think she was just trying to be friendly, but God knows what in her mind made her think it was appropriate to pull a gun—even a fake one—on an amputee,” van Agtmael said.

This full-on confrontation of uncomfortable moments, and the dual focus on war’s effects both at home and abroad, make Disco Night Sept 11 unique among war photography books. There are some interesting parallels in the book: for example, people are tangibly disconnected from the war in places both at home and abroad. In Iraq, van Agtmael photographed a soldier riding a family’s donkey in a tiny town outside Mosul where “they didn’t know there was a war on, they thought we were Russians and just wanted us to get the hell out.” In the U.S., he attended a 2010 military funeral where few people showed up. “I think we paid lip service to caring about these wars in the first place, but at this point in the war, in this small town, people had forgotten,” he said.

Committed to words too, van Agtmael has generously captioned his photographs in the book and includes other text ranging from diary entries to graffitti and transcribed conversations. He did this, he said, because “as much as photographs can say things words can’t, the reverse is true.” Photographs can also be deceptive: “Sometimes you have these profound experiences and they’re just not pictures, and then you have these meaningless experiences and they’re beautiful pictures.”

Committed to words too, van Agtmael has generously captioned his photographs in the book and includes other text ranging from diary entries to graffitti and transcribed conversations. He did this, he said, because “as much as photographs can say things words can’t, the reverse is true.” Photographs can also be deceptive: “Sometimes you have these profound experiences and they’re just not pictures, and then you have these meaningless experiences and they’re beautiful pictures.”

(Later, during the Q&A, an audience member asked Filkins if he felt that his writing is enriched by images . “Any writer would want to have his or her book illustrated, because it brings it to life,” Filkins answered. Pressed about whether he’d ever had an image in mind that van Agtmael didn’t capture, Filkins was fulsome in praise of his younger colleague. “He got ’em all. Peter has an amazing eye,” he said. He then looked at van Agtmael and said, “I was very happy with the photos you took,” at which an abashed van Agtmael answered, “Well, you wrote a nice article too.”)

For van Agtmael, the image that perfectly expresses the book’s theme of dissonance—and which gave it its title—shows a marquee outside a banquet hall in upstate New York. He described how he’d been driving along the road by the hall in 2010, and was drawn by a sign reading DISCO NIGHT SEPT 11. “I’d been covering the wars for years by then, and I was feeling a deep disconnect from the populace here,” he said. “The sign said it all.”

I’ve interviewed quite a few war photographers (including James Nachtwey, Susan Meiselas, and Kate Brooks ) and I’ve found them all very thoughtful and dedicated, not at all the adrenalin junkies of popular lore. On the evidence of Friday’s talk, van Agtmael is the real thing. He was thoughtful and refreshingly honest, talking about the mild PTSD his experiences had left him with, and admitting he didn’t really understand his own “dark adolescent fantasy” of going to war.

It’s a truism that going to war changes a person, and it has left its effects on this young photographer. Going to Barack Obama’s first inauguration in 2009, van Agtmael captured an image of people huddled on benches, sheltering from a dust storm—much as if they were in Afghanistan. “I was very excited about this picture,” he said, “but when I came home and showed it to my Mom, she said, ‘Peter, why couldn’t you just enjoy the day like everyone else?'” The answer, of course, is that he couldn’t—and we should be glad for that.

————————————————-

Disco Night Sept 11 is available from Red Hook Editions and the Magnum Store .

Peter van Agtmael’s website is here .

48 comments on “ Dancing while Rome Burns ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

It’s interesting how pretty the pictures here are – the rich colors, the humor, and surrealism. They are cognitively dissonant with the horror of war. But I guess this is Agtmael’s point, or way of making his point: he’s just noting how completely weird it is that most of us Americans go on living our lives as if the terrible things aren’t really happening, or are somehow OK, really.

Absolutely, dpwe — and also, I think, that there is color, banality and humor even in the midst of war.

Many thanks to Peter van Agtmael and you, Sarah, for reminding us of the long-term hidden psychological wounds from which so many veterans suffer.

They deserve far more support from rest of us.

Indeed, Michael. The recent scandal that 40 war veteran patients died in Arizona while waiting for doctors’ appointments has put the Dept. of Veterans Affairs in the spotlight here. It’s tragic that veterans don’t get better care, and tragic that so many of them need it in the first place.

nice post on war soldiers

Thanks for stopping by!

G.I. General issue. ‘They were expendable’.

This is frankly amazing, from the quality of the writing to the directness of motif and theme. To say I was impressed, would be an understatement. I disagree with some, in that from my perspective van Agtmael’s point (as you have explained it) is that the horror of war is magnified by the ordinariness of it. I’ve read of similar phenomena in German during World War I, when people simply grew familiar with war. It was a way of life. Of course, now we’re talking about a war that I can’t remember beyond. That’s the horror: not that we go on living our lives, but that we still support it all. Fire trucks in New York say, “Support our Troops.” It’s the way that keeps in giving … not our lives.

I may be a tad upset to write coherently. If so, I apologize. This article moved me profoundly.

Wyatt, thanks so much for your deeply-felt comments and for the compliments. I’m so glad this article moved you, and I hope you will stick around and explore more of the site. The Literate Lens is a labor of love, and it’s comments like yours that make it worthwhile.

Gosh … thanks. I believe I’m now following you. It takes a lot to impress me these days, but you blew me away. I’m glad we have connected !

Great! In that case you’ll get each new article as an email, and there’s one coming out tomorrow morning. Thanks again and happy writing!

They say the war is over/finished but the job has only just begun. Iraq is no better off than it was before 2003… if anything she is worse when you consider the ordinary Iraqi attempting to go about his/her daily business.

Many great lives have been lost on both sides… I hope it will not be in for nothing.

Yes indeed, baghdad. In fact, Dexter Filkins recently wrote an article in The New Yorker where he explored the very issues you’ve mentioned here. So many lives, so much money and nothing to show for it…

And here’s the link to the article…

http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2014/04/28/140428fa_fact_filkins?currentPage=all

I will check it out now. Thank you.

Hopefully all will not be lost.

Thanks for this. It’s nice to see images that show God’s grace working in even the most difficult circumstances. I’m always amazed by how He turns every evil around for good.

interesting, dancing while rome burns , certainly is !

expressed well in a thoughtful manner.

Much appreciated!

war is an absurd condition which is part terrible, part comedy and all pain and little gain. Years from now our grandchildren yet born will not note the names, the places or the faces and look strangely at these pictures and wonder if they are real.

Thanks, this was a really moving read…… the pics are amazing.

You’re welcome, Desire!

Reblogged this on aknztiaz .

Thanks!

Reblogged this on Human Relationships .

Great, thanks!

How do you find a fresh outlook on this same war…good job! Bad war.

Good point!

I seldom can find visuals of a war ended,are the soldiers going about gathering the weapons and supplies, or are they barley mobile?, just wondering how the atmosphere was right after the war.

Great post and really amazing work done to capture some of the day-to-day realities of war. It’s true how people back home “lose interest” — this is a way to humanize the issues again.

Thanks! It’s great to see the response to this work, and that it has touched a lot of people. Thanks for checking in.

Reblogged this on oovekbk0710 .

Thanks!

Reblogged this on I'm not a hipster I swear and commented:

I thought it was interesting that many of the photographs show fairly mundane activities, instead of the harsh environment associated with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. I also liked that it shows war veterans and how they have dealt with the transition they must go through when they return home

Thanks! Peter does have some more “expected” war photographs in the book too, but I agree with you that he shows some angles that are often not covered in this genre.

Reblogged this on jason5creative .

oh my, these photos are just wonderful! Great job!

What a great series of photos showing what life is like outside of combat. I love the contrast of the seemingly ordinary surroundings occupied by soldiers. I have so much respect and admiration for the people who put themselves in harms way to document and tell these very important stories with their words and photography. Thanks so much for sharing.

Very moving and great pictures. I am military as well.

Thanks for stopping by! Glad they were meaningful to you.

No problem just being honest!

Reblogged this on The World of Momus .

Thanks!

Reblogged this on Thoughts and commented:

Magnum photographer Peter van Agtmael’s new book on Afghanisatan and the scars it has left. Looks like some really profound photography.

Thanks! I agree with your assessment.

Reblogged this on letitiaevents .

Thanks!

“they didn’t know there was a war on, they thought we were Russians and just wanted us to get the hell out.” This is just wow.

Thank you for the article. Beautifully written and interesting, I am glad to be introduced to this photographer..