Josef Albers and Nan Goldin, an Unlikely Duo

Josef Albers (left) and Nan Goldin (right)

What do Josef Albers and Nan Goldin have in common? Not much, it would seem. Albers, who was one of the principal forces behind the famed German art school the Bauhaus , was a courtly man known for his formal art and excellent teaching. Conversely, Goldin shot to fame as a wild child of the 1980s, a free (if troubled) spirit who channeled her and her friends’ messy experiences with sex, drugs and bohemia into her art.

Yet on a recent visit to the Museum of Modern Art, I found some intriguing similarities between bodies of work on show by these two artists. Though not exactly spiritual siblings, the two had some similar concerns and thought processes, particularly concerning the narrative potential of photography.

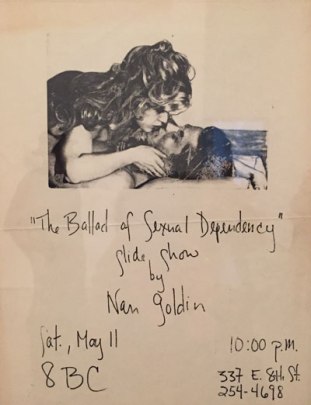

An early poster for The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency , long owned by the MoMA, is currently occupying a prime space on the museum’s first floor. The walls of the first two galleries put the work in context, displaying stills from the series and charmingly amateurish posters advertising early showings. But it’s really in the third room, a darkened theater showing the now-iconic slide show, that the work comes alive.

“ The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is the diary I let people read,” Goldin has written—and like a diary, the work is immediate, raw, confessional. It documents a world of excess and sensuality among East Village denizens of the 1980s, but along with the hedonism there’s a whiff of frenzy. As the New Yorker art critic Hilton Als wrote in this excellent profile of Goldin , Ballad “is poised at the threshold of doom; it’s a last dance before AIDS swallowed that world.”

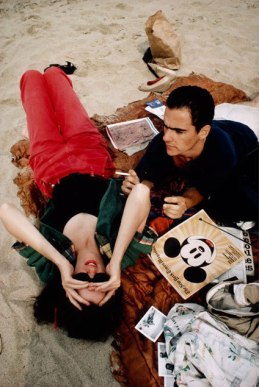

Twisting at My Birthday Party, New York City, 1980 , by Nan Goldin, from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

Accompanied by music from various eras—everything from the Velvet Underground to opera arias— Ballad scrolls by as a fever dream of highs and lows. The photographs themselves are as messy as their subjects, eschewing technical prowess in favor of spontaneity and access, as Goldin shows her friends shooting up, having sex, crying and being abused. But for every shocker of an image there’s a quieter one: what struck me on this viewing were the sections on masculinity and childhood, both of which are nuanced and reflective.

C.Z. and Max on the Beach, Truro, Massachusetts, 1976 , by Nan Goldin, from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

Ultimately, the power of the work comes from the cumulative effect of viewing it as the images build into a narrative, telling the story of a group of people at a particular juncture of time. There’s pleasure in recognizing characters who reappear, alone or in company, now jubilant and now in despair, and the layering and sequencing of images is complex. It’s a clever way of using photography’s capacity to freeze time while also subverting it, making viewers reassess their assumptions as they constantly build and rebuild a world from available fragments.

A similar force is at work on the museum’s fifth floor, in the small but satisfying exhibition One and One Is Four: The Bauhaus Photocollages of Josef Albers . Though it is as modest and quiet as Goldin’s work is in-your-face and operatic, Albers’ photocollages showcase a similar preoccupation with intimacy and narrative sequencing.

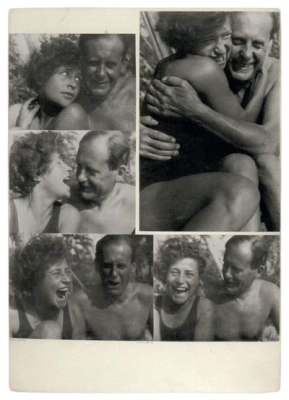

Walter Gropius and Schifra Canavesi, Ascona, August 1930 , by Josef Albers

Like Goldin, Albers took candid photographs of his friends, most of whom were artists. They are pictured at happy times—sunbathing, laughing, hugging each other—and at more reflective moments, smoking or looking into the distance. The way he carefully mounted the images onto board, finding playful and revealing sequences, implies that he had a theory of photographic portraiture that, like Goldin’s, focused on narrative-building.

“One and one is two—that’s business,” Albers wrote in 1938, in an elegant explication of this theory. “One and one is four—that’s art—or if you like it better—is life. I think that makes clear: the many-fold seeing, the many-fold reading of the world makes us broader, wider, richer. In education, a single standpoint cannot give a solid firm stand. Thus, let us have different viewpoints, different standpoints. Let us observe in different directions and from different angles.”

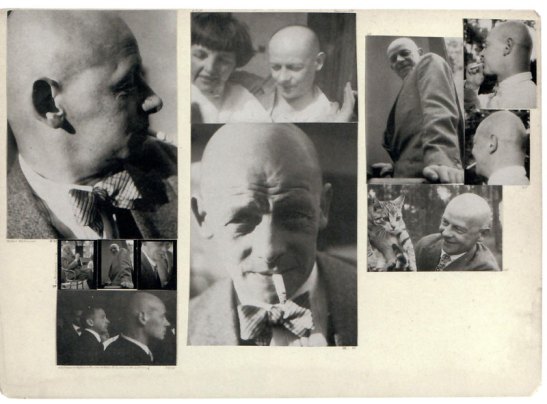

Oskar Schlemmer, 1927-1929 , by Josef Albers

In addition to this Cubist-like idea of portraits built from multiple angles, there’s a certain similarity in subject matter. Walter Gropius, who established the Bauhaus in 1919, did so after being trapped for three days in the rubble of a World War One bomb blast. His vision was to break from the past and build a new world, one based on nascent European Modernism. If the avant-garde artists he gathered around him were less wild than Goldin’s punks and drag queens, they were still classed as “degenerate” by the Nazis. And they enjoyed a good party too. Gropius called for “friendly relations between masters and students outside of work, therefore plays, lectures, poetry, music, costume parties. Establishment of a cheerful ceremonial at these gatherings.”

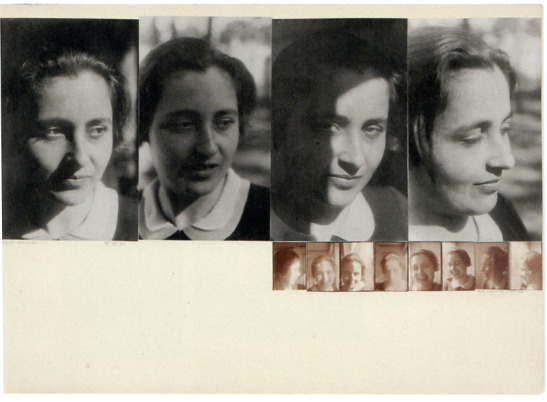

Albers’ portrait of Marli Heimann, a weaving student at the Bauhaus, shows this spirit of fraternization at work. Taken during the course of an hour, the twelve frames in the collage show different moods passing over Heimann’s expressive face. Albers varies the lighting, too, using full sun in one frame and, in its neighbor, a dramatic shadow covering a third of the subject’s face. Judging by his 1963 book Interaction of Color , Albers probably used the shadow for its shape and tonal contrast, but it could also be read metaphorically, as the oncoming darkness of the new political regime.

Marli Heimann, March [or] April, 1931, all during an hour , by Josef Albers

Unlike Goldin, Albers did not show these photocollages during his lifetime. But the discipline and artistry with which he assembled them suggests that he saw them as more than just a pleasing hobby. “In musical compositions, so long as we hear merely single tones, we do not hear music,” Albers wrote in his seminal 1963 book, Interaction of Color . “Hearing music depends on the recognition of the in-between of the tones, of their placing and of their spacing.” Placing, spacing: capturing shifting patterns and complex moods. This is something both Albers and Goldin embraced, and the art world is richer for it.

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is on show at MoMA through April 16, 2017. Find information about it here .

One and One Is Four: The Bauhaus Photocollages of Josef Albers is on show at MoMA through April 2, 2017. Find information about it here .

One comment on “ Josef Albers and Nan Goldin, an Unlikely Duo ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

I love the parallel! Both artists are complimented by the comparison, yet I doubt either would be grateful.