Visualizing Social Change

Social change and photography have always had something of a symbiotic relationship. “Concerned” photographers need movements, protests and problems at which to point their cameras, and change-makers need their causes witnessed and recorded. Accordingly, some of the most powerful social documentary photographs—from Dorothea Lange’s iconic Migrant Mother to its modern-day analog below—depend on collaboration, or at least acquiescence between subject and photographer.

Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange (left), and a modern-day analog featuring Syrian refugees at the Greek-Macedonian border (photo: AFP/Getty Images)

Obviously, there’s no shortage of subject matter for social documentarians these days. As we’re constantly told, we’re at a pivotal moment in history—here in New York, it seems that hardly a day goes by without an opportunity to protest, boycott or occupy something. How will we record today’s movements for social change? In different ways, two exhibitions I viewed recently offered perspectives on this question. One showed that resistance is not a new phenomenon, while the other presented groundbreaking ways of visualizing current social issues.

The Bronx Documentary Center

Whose Streets? Our Streets! New York City 1980-2000 at the Bronx Documentary Center is a reminder that social turmoil and resistance are not unique to this moment. The two decades chronicled by the exhibition were a particularly turbulent period in New York City, marked by economic disparity, poor race relations, police brutality, a housing crisis, and tension over the AIDS epidemic, abortion rights and the arts. Protests were rife, focusing not just on problems at home but also abroad: there was vigorous resistance to U.S. involvement in Central American wars and the nuclear arms race, and heartfelt support of liberation movements around the world.

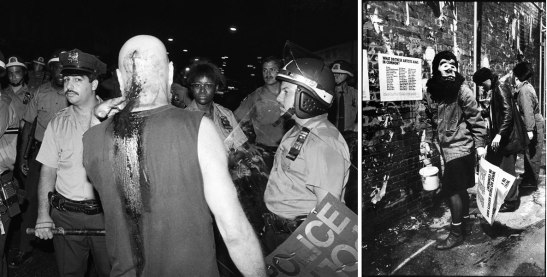

The show features the work of thirty-eight photographers, united by their commitment to get close to the action. Some of the work is artistically composed, some more rough and spontaneous, preoccupied with capturing the energy and passion of the moment. Some of it—like James Hamilton’s shot of a bloodied protestor walking towards police during a riot in Tompkins Square Park—reminds us of how fragile democracy can be. Other work, like Lori Grinker’s shot of the underground feminist group The Guerrilla Girls, who protested sexism and racism in the art world while wearing gorilla masks, showcases the creative spirit that protestors brought to bear on contentious issues.

Left: A riot in Tompkins Square Park, Manhattan, 1988, (c) James Hamilton. Right: The Guerrilla Girls wheat-paste posters in New York after midnight, (c) Lori Grinker/Contact Press

I hadn’t been to the Bronx Documentary Center before, and was happy to discover it—especially with this dynamic exhibition that at once plunged me back into challenging times (I came to New York City in 1989) and seemed so relevant to today’s political climate. The center was founded in 2011 by Mike Kamber, a New York Times photojournalist who wanted to create a community and educational space in one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. Whose Streets? Our Streets! ends tomorrow, but a permanent website has been put up here so that viewers can learn more about the issues and photographers behind the show.

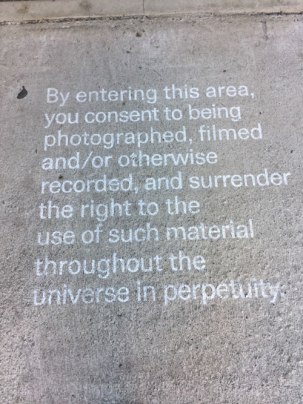

Sign at the entrance of the ICP

At the other end of the city, a wide-ranging show at the International Center of Photography, Perpetual Revolution: The Image and Social Change, looks at some ways photographers are carrying forward the legacy of their social documentarian forebears. The exhibition is organized into six “modules,” or subject areas: climate change, the refugee crisis, gender fluidity, ISIS propaganda, #BlackLivesMatter, and the alt-right’s effect on the 2016 presidential election. In each section, new methods of image production and dissemination are highlighted, pointing to ways in which visual storytelling, activism and propaganda are changing in our tech-driven times. This marks the ICP’s mission expansion—along with its move downtown to the Bowery—to expand its coverage from still photography to the more topical and dynamic framework of “visual culture.”

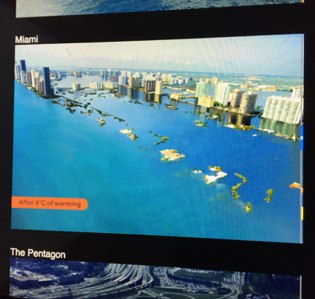

The potential effects of sea level rise on Miami, (c) Climate Central/Nickolay Lamm

This worked particularly well in the section on climate change, where new methods of presentation can highlight rapid changes. A collaboration between nonprofit organization Climate Central and artist Nickolay Lamm, Sea Level Rise Project, showed the potentially disastrous effects of sea level rise on major cities; James Balog’s footage of a calving glacier in Greenland was similarly terrifying. Urgency was conveyed, too, in Mel Chin’s beautiful and quietly devastating film The Arctic is Paris, in which Jens Danielsen, an Inuit from Greenland, comes to Paris with his sled to warn of the chaotic effects of rising temperatures. In a topical twist, the film was made just after the November 13th, 2015 ISIS attacks in Paris, and includes footage of mourners outside the Bataclan theater.

A screenshot from Mel Chin’s film The Arctic is Paris

Some of the other sections were at times uneven. In the one on the refugee crisis, Hakan Topal’s Untitled (Ocean), which projected found images of refugees onto a bumpy surface meant to evoke the rocks of the Syrian-Turkish border, was stylish but vague, an attempt at “experiential” viewing that didn’t quite work for me. (Much more involving was the story of Thair Orfhali, a Syrian refugee, former law student and unfailingly cheerful guy who documented his perilous journey to Germany on his smartphone.) And the section on #BlackLivesMatter, Black Lives Have Always Mattered, seemed a little static and sedate given the outrage of the movement’s members, though I appreciated its effort to place the current situation within a historical continuum.

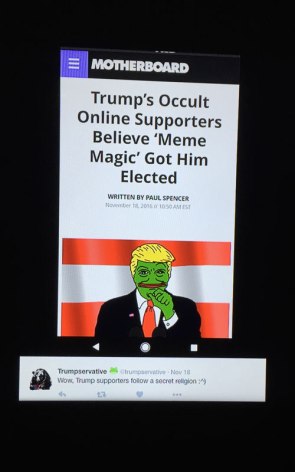

This screenshot shows how the Trump campaign adopted Pepe the Frog, a white supremacist symbol

The two last sections, on ISIS propaganda and the alt-right, were downright terrifying—reminders of how imagery can be used to drive forward a radical agenda. Unlike work in other sections, the imagery here was not meant to be shown in a gallery, but rather to be disseminated widely online. Looking at these vile campaigns felt a bit voyeuristic and surreptitious, but clearly important, because future campaigns will be waged on the strength of social media imagery and power.

For me, this exhibition was more successful than its predecessor in the new space, Public, Private, Secret, a similarly wide-ranging show that fell on the sword of its own ambition, ending up by looking somewhat messy and chaotic. The six curators of Perpetual Revolution reined in it, going for a cleaner, more organized look. Clearly, each module could have been expanded to form an entire show, but this is a case of more being more: the cumulative effects of the six sections were at once enlightening, thought-provoking and devastating.

The International Center of Photography’s new museum on the Bowery

Most importantly, both of these exhibitions felt vibrant and highly relevant. Increasingly, our world is splintering into factions, and our ability to convey points quickly and viscerally will govern who gets to call the shots. Visual culture has always had the power to sway hearts and minds. Now it is more important than ever.

Whose Streets? Our Streets! New York City 1980-2000 is on show at the Bronx Documentary Center through March 5. More information can be found here and here.

Perpetual Revolution: The Image and Social Change is on show at the International Center for Photography until May 7, 2017. For more information, click here.