Rockwell Redux: An Interview with Maggie Meiners

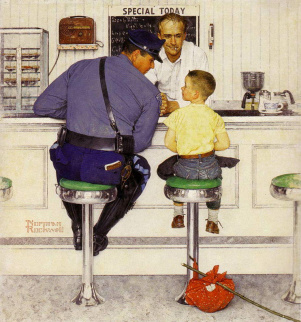

The Runaway , 1958, by Norman Rockwell

What comes to mind when you think of Norman Rockwell? Chances are, that name conjures up reassuring images of 1950s Americana, with subjects ranging from soda fountains to baseball games to apple-cheeked kids. Rockwell was renowned for such images, which appeared weekly on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post , making him the foremost visual chronicler of the American Dream.

But Rockwell had other layers too—as photographer Maggie Meiners found out when she began using his images as inspiration. In 2012, Meiners began a series called Revisiting Rockwell , cleverly updating the iconic images for our times. In Meiners’ reenivisioning, Rockwell’s telephone gossipers become texters, his black-eyed tomboy becomes a transgender child, and his black girl being escorted to school becomes a Latina girl being deported.

Norman Rockwell’s The Gossips (left) and Maggie Meiners’ It Went Viral (right)

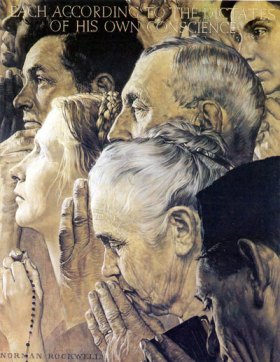

Last year, I interviewed Meiners for an article about women photographers’ support groups and networks that appeared in Photo District News. After that, we became Facebook friends, and I followed her progress, which is how I happened to see her moving and beautiful updating of Rockwell’s Freedom of Religion . While Rockwell’s image features a lone Jew among differently-denominated Christians, Meiners’ image shows a group of Muslim-Americans praying together. Purposefully, she posted it on Facebook on the day Donald Trump was inaugurated, inviting comparison with the new president’s deprecating comments about Muslims.

Intrigued by that image, and by the series as a whole, I interviewed Meiners earlier this week. Our wide-ranging conversation touched on everything from hearing loss to the production and dissemination of a socially-conscious image like Freedom of Religion .

I read that you suffered from profound hearing loss as a child. How did that come about and how has it shaped you as an artist?

Lite Brite , by Maggie Meiners

It came about from a lot of ear infections, surgeries and scar tissue. I didn’t become an artist until later in life, in my early thirties, and I think I just became more visually aware because my hearing had gotten to a point where it was so bad that I was relating to the world primarily through my eyes—reading lips, focusing on gestures and visual cues. I’d had hearings aids in college, but I put them aside for a while and then got them again in my thirties. Ironically, being able to hear better gave me confidence to engage in the world from a more creative, visual place.

What did you do before becoming a photographer?

I was a middle school Social Studies and English teacher. My background in college was Cultural Anthropology, and I always had an interest in subcultures and social rituals.

4 Square , by Maggie Meiners

A lot of your early work was abstract in nature, very different from the Rockwell work…

Yes. I think it was part of a spiritual journey. I’d had some issues with addiction and depression, and that, along with my hearing loss, made relating to the world pretty hard at times. Trying to regain some control led me to the more abstract work. Then as I found myself recovering from some of those darker times, I was willing to engage with more of the world.

What made you decide to do the Rockwell series?

In 2010, I was at the Norman Rockwell museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts with my kids and husband. I noticed that the paintings were really sparking conversations among museumgoers, and I thought it was great that they were so accessible. At one point our family was looking at the famous painting Freedom from Want , and it the time when Proposition 8 (to legalize gay marriage) was on the ballot in California, and we have a brother who was very involved with that. We started talking to our kids about Uncle Matt and Prop 8, asking questions like, What makes a family? Who decides? It was a very fruitful discussion, and afterward I said to my husband, Wouldn’t it be cool to recreate this image as a photograph? He said, You should totally do it. That was the impetus, though I didn’t start until 2012 and didn’t recreate Freedom from Want until much later, because it had so many people in it and that was intimidating.

Freedom from Want , by Norman Rockwell (left) and Maggie Meiners (right)

What was the first painting you recreated?

The tattoo artist. It seemed like the simplest. I had a green screen and I could get a tattooist, and a model. It grew from there. I knew I was going to do a series, and I’d lined up a sort of order in my head. I started off simple because I don’t have a lot of training in lighting and styling, and for the more complex images I needed a team.

Pride , by Maggie Meiners

What came after the tattoo artist?

I think it was Outside the Principal’s Office , which I called Pride . My son was the model for that. He’s wearing a wig because I wanted to hone in on the issue of transgender kids. Simultaneously, I was working on It Went Viral , an updating of The Gossips .

It’s really clever how you updated The Gossips , using cellphones and texts instead of the telephone. It shows how things change and yet stay the same.

Exactly. Through doing this series I’ve learned that, while on the surface there are some very obvious changes since the 1950s—in technology, dress, women being in combat, et cetera—there’s a lot that’s stayed the same. I realized in particular that I don’t have a lot of diversity in my life. Being an artist and involved in civic life, I do come across different kinds of people, but otherwise, I live in the Chicago suburbs where it’s all very homogenous, both racially and socioeconomically. At one point I went to a portfolio review with the early work, and the reviewer said, I don’t see any diversity in your images. My response was, I don’t have a lot of diversity in my life!

You’ve certainly made up for that in some of the more recent work. In your recreation of Freedom from Fear , you replace Rockwell’s lily-white family with a black mom and her kids. Can you talk about that image?

Cock, Bang and Repeat , by Maggie Meiners

The original has two white parents looking over their sleeping kids, and the man is holding a newspaper with a headline about the atomic bomb. We’d had a couple of very violent summers in Chicago, and I was talking to an African-American woman whose kids take music classes with mine. Her husband wasn’t comfortable modeling for me, but she was, and she liked the concept. I changed the newspaper title to reflect what was going on in Chicago. A lot of young people were being shot by police, and the mothers were terrified. My title— Cock, Bang and Repeat —might sound a bit flippant, but I was referring to shampooing (wash, rinse and repeat) and the fact that these shootings were becoming so routine.

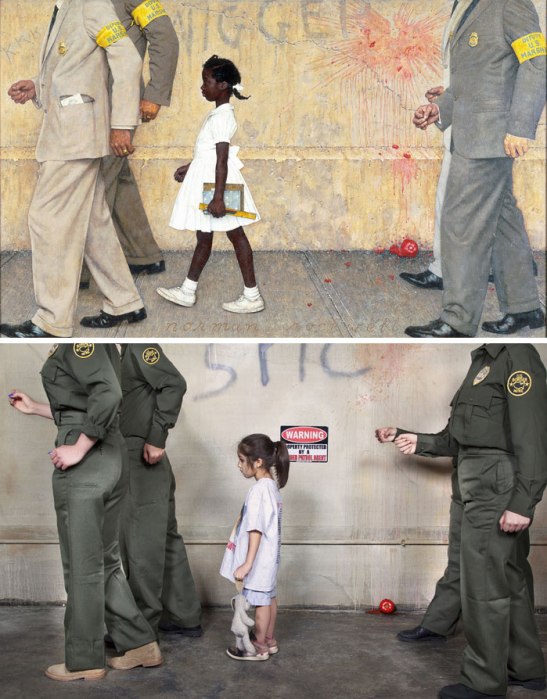

Rockwell did take on some political issues himself. His painting The Problem We All Live With shows a young girl, Ruby Bridges, being escorted to school by the National Guard in the Civil Rights era. Again, you updated that very cleverly in your image Dream Act : your little girl is Latina and is presumably being taken away for deportation.

Immigration was very much in the news at the time, and there was a lot of talk about the Dream Act. I feel like had a bit of foresight with this, because it occurred to me that the issue was far from over, and would end up being a bigger problem than we thought. This whole project has been very interesting in that it started in 2010, and the issues have become more and more relevant.

The Problem We All Live With , by Norman Rockwell (top), and Dream Act , by Maggie Meiners (bottom)

Yes, indeed. Your most recent image, Freedom of Religion , is pretty much ripped from the headlines. It’s a complex, beautiful image of Muslim-Americans praying. How did you pull it off?

Freedom of Religion , by Maggie Meiners

I belong to a church, and we had an adult education program where a visitor came out to talk about being Muslim-American today. I didn’t attend the talk, but I reached out afterward to my pastor and asked him to put me in touch with this man. Dawood and I met for coffee, I showed him my other work and explained what I was trying to do, emphasizing that I wasn’t trying to be offensive in any way. He got the models for me; one of them is his daughter. It was a real collaboration. He was very good about trying to find people with different skin tones. He himself was born on a farm in Iowa, to a Caucasian mother, so he’s light-skinned, and then he has friends from Somalia. It was my most nerve-wracking shoot because I didn’t know any of the models and I had to hire a studio, a make-up artist, a couple of assistants, and a lighting person. I directed and produced and didn’t touch the shutter. To let go of that control was hard.

You posted the image on Facebook on Inauguration Day, which in itself was provocative. What has the reaction been?

Freedom of Religion (or Freedom of Worship ), by Norman Rockwell

It gives me goosebumps to think about it, because so many people have been so positively impacted by it. I became Facebook friends with the models, and they sent it out to their communities. I did sponsor the post, because you can target certain areas of the country and I wanted to see what would happen. I had some Internet trolls from Louisiana and Mississippi, but that was the only negative. I should mention that for any sales from this image, after my gallery gets its cut I’ll be giving all the rest to a Muslim-American education center and a Muslim-American food pantry that Dawood suggested. I’m really happy about that. It’s nice to sell your work and get a profit, but I feel that this one isn’t about me.

What do you hope people get from this image in particular and the series as a whole?

I really just hope that it fosters dialogue, and opportunities for people to see art as a way to create ideas, discussion and possibly, legislation. I think using art can be a safe way for people to discuss ideas and values. I’ve never worked this way before, and the other work I’ve done is so different that I’m not sure quite what to expect. But I hope these images will be a platform for people to use as discussion, just like the original paintings in the Rockwell museum. It’s a great way to connect with a stranger!

Rockwell Revisited is currently on exhibition at the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio, through Feb. 26.will be on exhibition at the Southern Vermont Arts Center in Manchester, Vermont, from September 16-November 5, 2017 .

25 comments on “ Rockwell Redux: An Interview with Maggie Meiners ”

Information

This entry was posted on February 10, 2017 by sarahjcoleman in Art Photography , Exhibitions , Interviews , Uncategorized and tagged Cock Bang and Repeat , Dream Act , Freedom from Fear , Freedom from Want , Freedom of Religion , It Went Viral , Maggie Meiners , Norman Rockwell , Outside the Principal's Office , Pride , The Gossips , The Problem We All Live With .Shortlink

https://wp.me/p25Qfq-3wmRecent Posts

Archives

Categories

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Join 11,055 other followers

This is beautiful and inspiring work.

Such a creative use of your experiences! Inspiring!

Up is beautiful

So cool 😎

Creativity and inspiring… The lady smiling on the right of N. Rockwell’s “Freedom from Want” is the Mother of my best friend, her grandfather, the bold gentleman, is on the left of the painting. Isn’t that amazing…

Reblogged this on sailorpoet and commented:

I want to share this one without commentary and let the art and words of the artist speak for themselves. If I were to comment, absolute brilliance.

WOOOOOOOOOOOOOOWWW beautiful

This very nice spring word than I ever seen.

Absolutely loved the recreation of “Freedom From Want”!!

This is beautiful and inspiring work.

Very nice post and very informative and creative

Very nice post, it looks like an interesting exhibit as well. I shared it in my Twitter feed.

Great work !!!! Inspiring !

So creative

I’m so impressed with this work. I’ve been a fan of Rockwell for years. This tops it.

I just love this!

Nice work!!!

Incredible work. Ingenious.

Amazing

Amazing(check out some of my work) thanks! Awsome job again.

Awesome job! Congrats!

Wow, these are wonderful

Fascinating project. I would like to see more. Has she done a “Self Portrait”?!

But see how static Meiners’ image is compared to Rockwell’s in “The Problem We All Live With”

Michael, she has indeed done a ‘Self-Portrait’ in the Rockwell style: see http://www.maggiemeiners.com/revisiting-rockwell for that any many others.

You’ve written the nice post, I am gonna bookmark this page, thanks for the info. I actually appreciate your own position and I will be sure to come back here.