Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Art of Subversion

This is a guest post by Jennifer Cody Epstein .

Last July, Donald Trump drew ire when he criticized the family of Humayun Khan (above), a Muslim-American soldier slain in Iraq.

In the run-up to the presidential election last November, few of Donald Trump’s proposals sparked quite as much alarm as his idea for a Muslim “registry.” The idea has undergone several iterations—from requiring the registration of Muslims in America, to registering people from a list of almost exclusively Muslim nations, to banning Muslims from entering the country altogether—but at their core, each version hearkens back to one of America’s darkest moments, the forcible evacuation and internment of thousands of Japanese Americans civilians following America’s entry into World War II. In fact, in the days after the election, Trump surrogate Carl Higbie actually cited the internment program as “precedent” for the proposed Muslim database.

The registry talk has died down somewhat since then. But with the inauguration fast upon us (or perhaps over by the time you read this), and Trump’s newly-formed cabinet boasting a security advisor who has called Islam “a cancer,” it seems like a good time to revisit this so-called “precedent.” And there are few better ways to do this than through the extraordinary story of Dorothea Lange’s government-suppressed photographs of these American-style concentration camps–and their mostly-American residents.

1942, San Francisco, California. Residents of Japanese ancestry appear for registration prior to evacuation. Photograph (c) Dorothea Lange.

The internment program was the result of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 . Signed on February 19 th , 1942, the order authorized the designation of swathes of the West Coast as “military zones” from which the government had the right to evacuate potential “enemy aliens.” As a result, over 134,000 American citizens and residents were abruptly uprooted from their lives, piled into heavily-guarded trains and deported to twenty-one makeshift camps across the country. While some of these “aliens” were of German and Italian descent, over 120,000 of them were Japanese Americans—and over two-thirds of those were American-born citizens. (That the rest were not was in large due to a U.S. law barring Asian immigrants from naturalization at the time.)

May, 1942-Hayward, California. Members of the Mochida family await an evacuation bus. Mr. Mochida operated a nursery and five greenhouses in Eden Township where he grew snapdragons and sweet peas. Photograph (c) Dorothea Lange.

The order was the culmination of a nationwide wave of hysteria, political fear-mongering and anti-Japanese press that cast Pearl Harbor in almost exclusively racial–rather than political–terms to the public. It clearly mattered little that such frenzy contradicted F.B.I. and military reports concluding that Japanese-Americans posed no security risk to the war effort. For General John Dewitt of the Army’s Western Defense command, the Japanese were “an enemy race, and while many second and third generation Japanese born on American soil, possessed of American citizenship, have become ‘Americanized,’ the racial strains are undiluted…It therefore follows that along the vital Pacific Coast over 112,000 potential enemies, of Japanese extraction, are at large today.” The L.A. Times picked up the drumbeat, opining that “a viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched, so a Japanese-American, born of Japanese parents—grows up to be a Japanese, not an American.”

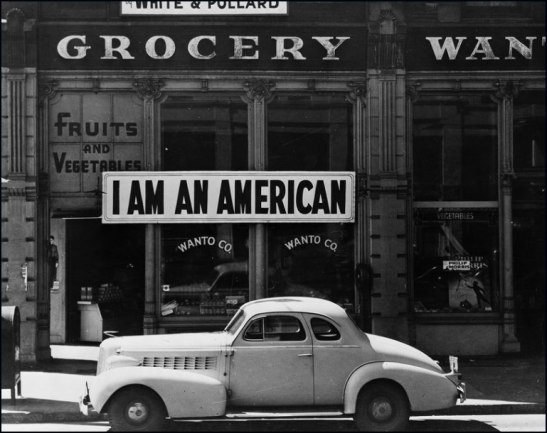

March, 1942-Oakland, California. A large sign reading “I am an American” placed in the window of a store at 13th and Franklin streets on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor. The owner, a University of California graduate, will be housed with hundreds of evacuees in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration of the war. Photograph (c) Dorothea Lange.

Lange in 1936, during her work for the FSA. Photographer unknown.

Lange was hired by the War Relocation Authority following her acclaimed work for the Farm Security Administration documenting migratory farm laborers, which included her iconic portrait of Florence Owens Thompson, Migrant Mother . Her mission for the FSA had been to visually present the hardship in her subjects’ lives, but the WRA was likely seeking the opposite; to show that its program was not mistreating internees or violating international law. Unknown to her employer, however, Lange–who had several Japanese American acquaintances–was personally opposed to the internments, and used the opportunity to document the program’s injustice and inhumanity.

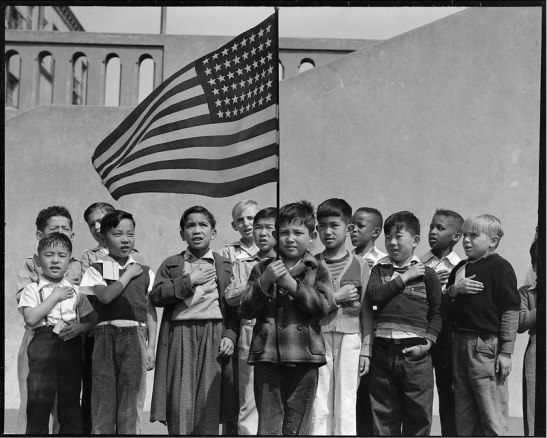

Over the course of six months and at twenty-one locations, she ended up capturing some of the most poignant moments recorded of the event. Often, she instructed her subjects to look away from the lens or at the ground in order to emphasize their anxiety and despair. Craftily, she also included elements like American flags, U.S. Army and Boy Scout uniforms, baseball and cowboy hats, thereby highlighting the American-ness of these “enemy aliens.” She captioned the images herself, often with a quiet inflection of outrage that further expressed her views.

1942, San Francisco, California. Flag of allegiance pledge at Raphael Weill Public School, Geary and Buchanan Streets. Photograph (c) Dorothea Lange.

It was a subtly subversive approach, and one that required an impressive balancing act: on the one hand presenting a front of artistic impartiality, on the other navigating a gauntlet of WRA-imposed restrictions designed to censor and control Lange’s work. She was allowed no shots of wire fences, watchtowers, searchlights, camp guards or any form of detainee resistance, and was discouraged from even talking to her subjects. Despite these constraints, though, she managed to take over 800 photographs that, together, unflinchingly tell the story of this grim moment in American history.

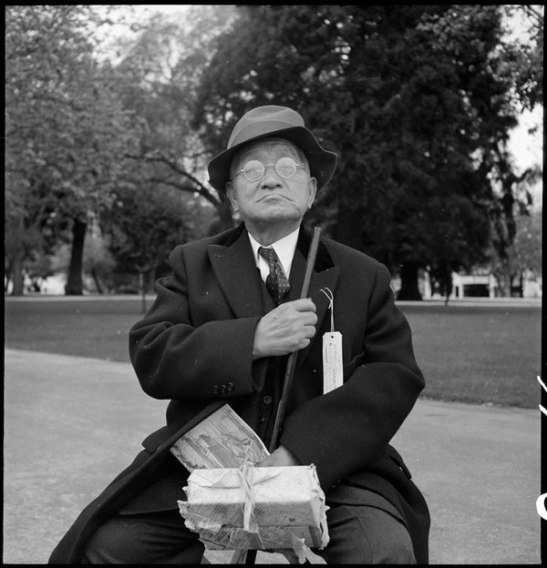

May 8, 1942-Hayward, California. Grandfather of Japanese ancestry waiting at a local park for the arrival of evacuation bus which will take him and other evacuees to the Tanforan Assembly center. He was engaged in the cleaning and dyeing business in Hayward for many years. Photograph (c) Dorothea Lange.

Florin, Sacramento County, California. A soldier and his mother in a strawberry field. The soldier, age 23, volunteered July 10, 1941, and is stationed at Camp Leonard Wood, Missouri. He was furloughed to help his mother and family prepare for their evacuation. He is the youngest of six children, two of them volunteers in the United States Army. The mother, age 53, came from Japan 37 years ago. Her husband died 21 years ago, leaving her to raise 6 children. She worked in a strawberry basket factory until last year, when her children leased 3 acres of strawberries “so she wouldn’t have to work for somebody else.” The family is Buddhist. 453 families are to be evacuated from this area. Photograph (c) Dorothea Lange.

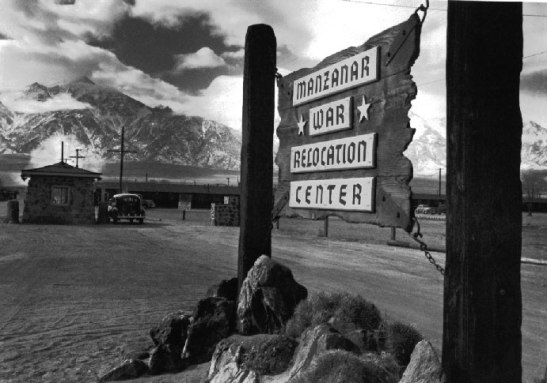

As an approach, it was in striking contrast to that of Ansel Adams, who was to document life at California’s Manzanar War Relocation Center in 1943. While he later claimed to have also opposed the internment program, he portrayed his subjects in a distinctly hopeful and even cheerful light, often set against the majestic backdrop of the Sierra mountains.

1943-Manzanar, California. Gateway to War Relocation Center. Photograph (c) Ansel Adams.

Upon completion of the project, the WRA—no doubt realizing that it had been duped–confiscated the entire collection of Lange’s images, suppressing the photographs (as it suppressed their subjects) for the rest of the war’s duration. For the following six decades the pictures remained buried in the National Archives. A decade ago, however, 119 of them were published in W.W. Norton’s Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment . They can now also be found online, on NPS’s Manzanar National Historic Site , the University of California’s Japanese American Relocation Digital Archive and the blog AnchorEditions.com , where blogger Tim Chambers has juxtaposed them with historical quotes. These include first-hand accounts by internees themselves, such as that of Yoshiaki Fukuda, a church minister from San Francisco: “Although we were not informed of our destination, it was rumored that we were heading for Missoula, Montana..… The view outside was blocked by shades on the windows, and we were watched constantly by sentries with bayoneted rifles who stood on either end of the coach. The door to the lavatory was kept open in order to prevent our escape or suicide.… There were fears that we were being taken to be executed.”

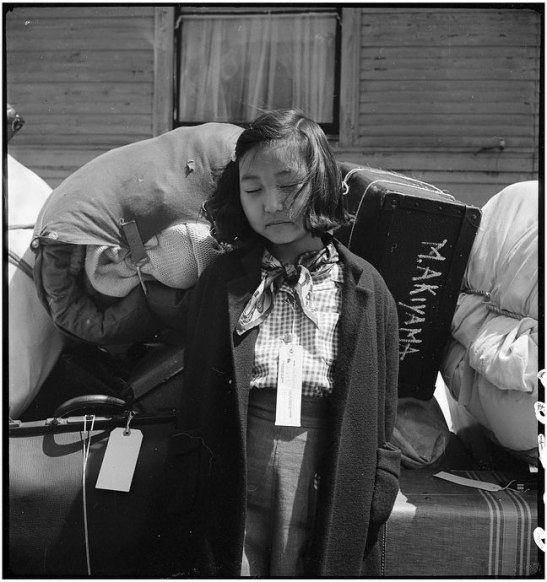

1942-Oakland, California. Kimiko Kitagaki, young evacuee guarding the family baggage prior to departure by bus in one half hour to Tanforan Assembly center. Her father was, until evacuation, in the cleaning and dyeing business. Photograph (c) Dorothea Lange.

Chambers—who is also a photographer–is now making some of the images available for purchase as reprints . He is also donating half the proceeds to the ACLU. It’s a gesture that also seems particularly timely, for while Trump hasn’t recently reprised his registry talk the subject remains very much in the public eye. Just this past month, over 2200 employees from tech companies ranging from Amazon to Yahoo added their names to an online pledge not to help Trump’s administration create such a registry. “We have educated ourselves on the history of threats like these, and on the roles that technology and technologists played in carrying them out,” reads their statement . “We see how IBM collaborated to digitize and streamline the Holocaust, contributing to the deaths of six million Jews and millions of others. We recall the internment of Japanese Americans during the Second World War.”

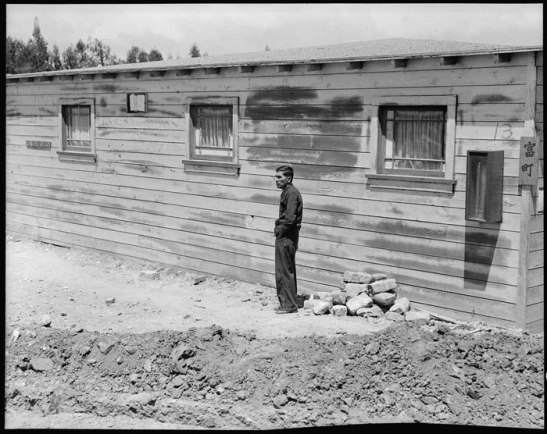

June 16, 1942-San Bruno, California. Many evacuees suffer from lack of their accustomed activity. The attitude of the man shown in this photograph is typical of residents in assembly centers, and because there is not much to do and not enough work available, they mill around, they visit, they stroll and they linger to while away the hours. Photograph (c) Dorothea Lange.

Ironically, the site went live just days before a dozen tech A-listers, including Apple CEO Tim Cook, Alphabet CEO Larry Page, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, Tesla CEO Elon Musk, IBM CEO Ginni Rometty and Intel CEO Brian Krzanich sat down with Trump and vice president-elect Mike Pence for a two-hour meeting. Officially on the agenda were jobs, immigration policy, China, cybersecurity and taxes. The summit sparked backlash from tech writers and political activists : “Full of ugly choices and likely bad outcomes,” wrote Recode.net excutive editor Kara Swisher of the attendant tech leaders, “they have opted to punt, with most of them saying nothing publicly about even attending the summit nor making it clear beforehand that there are some key issues that are just not negotiable.” And theVerge.com ’s Vlad Savov scoffed that the attendees “all took part in the contrived parade of paying fealty to Trump’s new power… Somehow, the greatest titans of the tech industry have shrunk to the size of mute mice in the shadow of the incoming president.”

Summit attendees were also mute on whether the Muslim registry issue came up. But they did reportedly agree to future meetings with Trump. One can only hope that those meetings won’t end up circling back to the ugly path that Lange so bravely and vividly chronicled for us.

Jennifer Cody Epstein is the author of the international best-selling novel The Painter from Shanghai , and the widely-acclaimed The Gods of Heavenly Punishment . She lived for five years in Japan, first as a student and then as a journalist. She now lives in New York with her husband and two daughters.

2 comments on “ Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Art of Subversion ”

Information

This entry was posted on January 19, 2017 by sarahjcoleman in Books , Documentary Photography , Historical Sites , Uncategorized and tagged ACLU , Ansel Adams , Donald Trump , Dorothea Lange , Japanese-American internment , Manzanar , Manzanar War Relocation Center , Tim Chambers , War Relocation Authority .Shortlink

https://wp.me/p25Qfq-3uoRecent Posts

Archives

Categories

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Join 11,055 other followers

Thank you for your reminder.

Thank you for a thoughtful post which makes the past very relevant to the current period. I like your contrast of of Lange’s and Adams’ approaches.