Close Encounters of the Theatrical Kind

Earlier this month, I wrote about how photographers and organizations were bringing elements of immersiveness and interactivity to their exhibitions at the Brooklyn festival Photoville . Though I didn’t plan it, this post will continue that theme. Yesterday I saw The Encounter , a new Broadway play about 1960s National Geographic photographer Loren McIntyre . Fresh from a sold-out run in London, The Encounter uses cutting-edge aural technology to create an immersive soundscape. It was surprising, and exciting, to see such an experimental piece on Broadway, which typically offers more conservative fare.

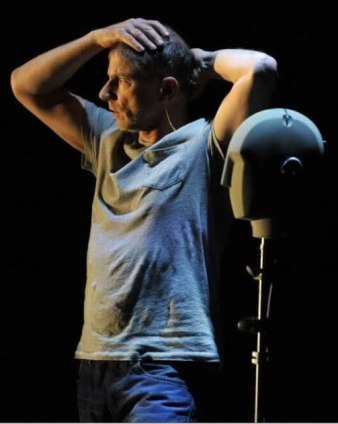

Calling The Encounter a play is perhaps a bit misleading—like calling Godzilla a lizard. It’s more of an augmented monologue, a bravura performance by creator Simon McBurney , who interacts at various times with recorded voices but otherwise carries this 110-minute intermission-free show on his own. American audiences might recognize McBurney from film roles in the likes of Mission: Impossible and The Theory of Everything , but in the U.K. he is the co-founder and artistic director of Complicite , an experimental theater company known for its dynamic, unconventional productions.

The Encounter subverts theatrical tradition in many ways. From the moment McBurney steps onto the stage, with the house lights still up, it’s clear this will be unlike the typical theatergoing experience—so much so that he observes, “You’re wondering if it’s started yet.” Indeed, it has, but with a chummy, break-the-fourth-wall chattiness that makes it feel as if you’ve stepped into McBurney’s living room (he even texts a photo of the audience to his daughter, “to prove that I’m working.”)

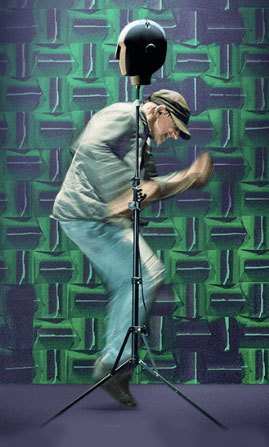

All of which is a warm-up to the moment of the big tech “reveal,” when McBurney invites audience members to don the headphones at their seat. His voice is now inside what he calls the “two and a half pounds of electrified paté” between our ears, but that’s not all: in the middle of the stage is a binaural head that acts as a stand-in for each viewer, and McBurney circles it to prove the aural illusion that he is speaking from just behind, beside and in front of us. “If I blow in your ear, it will even start to feel warm,” he claims, and I swear that my right ear heated up as he blew at that spot on the mannequin’s head. Judging by the laughter all around, there were a lot of warm ears in the house.

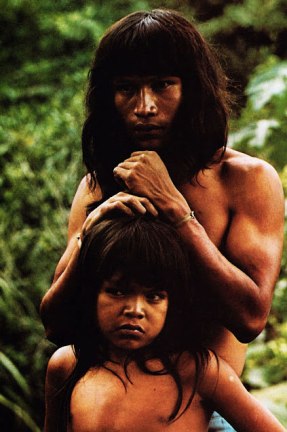

Having established this connection, McBurney gets into character as McIntyre, down-shifting his voice an octave or so and taking on a convincing American accent. It’s 1969 and McIntyre has just landed in the Amazon, in search of the elusive Mayoruna Indians. As a National Geographic photographer, he is seeking to uncover this hidden tribe and its customs—a job of whose ethical mire he’s aware. “I wonder what I’m starting,” he states, speculating that his photos could bring anthropologists and reporters descending on the tribe, changing its nature forever.

A Mayoruna Indian. The Mayoruna are also known as Matsés, or Cat People, for the spikes they insert in their faces.

We’ve seen self-doubting photographers portrayed in the culture before—from the majestic James Nachtwey in War Photographer to the young South African upstarts of The Bang-Bang Club . But McBurney has bigger ambitions than to simply explore these ethical swamps. He adapted the show from a book about McIntyre by Petru Popescu, called Amazon Beaming , which is part Moby Dick, part Heart of Darkness. In both book and play, what starts as a simple photographic quest becomes a journey to the edges of consciousness, time and sanity, as McIntyre disappears deep into the jungle with the Mayoruna and develops a telepathic connection to the tribe’s headsman, whom he calls Barnacle.

In short, there are lots of Big Questions posed by this production. On the level of the source material alone, questions of memory and record-keeping are interrogated after McIntyre’s camera breaks and he’s forced to reexamine his purpose. Though in many ways an imprecise instrument, the camera would have allowed him to show evidence of his trip. However, the Mayoruna believe that, with or without equipment, he is a recorder. When he asks Barnacle why he’s being kept alive, he is told that he’s there to “authenticate,” to be a witness to the tribe’s existence.

In short, there are lots of Big Questions posed by this production. On the level of the source material alone, questions of memory and record-keeping are interrogated after McIntyre’s camera breaks and he’s forced to reexamine his purpose. Though in many ways an imprecise instrument, the camera would have allowed him to show evidence of his trip. However, the Mayoruna believe that, with or without equipment, he is a recorder. When he asks Barnacle why he’s being kept alive, he is told that he’s there to “authenticate,” to be a witness to the tribe’s existence.

Thanks to the immersive sound environment, McBurney’s recreation of McIntyre’s journeys—both inner and outer—are uncanny. At all times, the illusion is on full view: we know, for example, that the actor is treading on thickets of unspooled video tape in a cardboard box, yet we’re transported to the claustrophia of a humid jungle where an explorer is crunching through a carpet of leaves.

We’re also constantly being pulled out of this illusion by McBurney, who uses the source material as a starting point to comment, with deadpan British wit, on everything from Cheez Doodles (“made with real cheese, and, one presumes, real doodles”) to the tyranny of technology. At one point, high on a psychoactive plant that the Indians have given him, McIntyre joins his hosts in a frenzy of destruction, which morphs into McBurney trying and failing to destroy his smartphone. “You know why we can’t get rid of our past?” he shouts, waving the phone. “Because it’s all backed up !”

Simon McBurney questions the pervasiveness of technology in The Encounter. Photo (c) Gianmarco Bresadola

In short, this is unlike anything else you’ll see on Broadway this year. I argued in my last post that photography exhibitions were becoming more immersive, and I’ve made that observation about art installations in the past. Whether or not The Encounter is part of a zeitgeist of new, immersive/experiential theater remains to be seen, since it’s on a bit of a leading edge, and since theater by its nature has an immersive quality. For me, the acid test question with technology in art is, Does it add to the story? Does it feel necessary?

In the case of The Encounter , I think the answer is yes: McBurney uses it to awaken our senses in a way that adds enormously to his storytelling. But I also feel that one has to be careful not to go crazy with the high-tech toys available these days—or at least, not to get so entranced by them that you neglect good writing. I can’t help wondering how self-conscious it was, on McBurney’s part, that he was bringing these technological bells and whistles to a performance in which he rails at the tyranny of modern technology.

I was curious about the source material, so after seeing the play I bought Amazon Beaming (on my electronic device, of course) and started reading. I was surprised and delighted to discover a beautifully written account of McIntyre’s adventure, full of inventive storytelling and lush descriptions. I’ll leave you with a passage from the book:

Loren watched, arrested by the symbolism of the scene. Early man had gained the concept of succession, the earliest symbol of the passing of time, by observing natural phenomena. The dripping of water from natural faucets, the repeated call of birds, man’s own heartbeat, his own footsteps. They had been man’s first clues that time existed as a pulsing vein, invisibly uniting all life. From such early rhythms of nature, dance was born, to stay with man forever.

…He watched Tuti dancing the dance of the rain. Devising a game and an interpretation of reality out of thre drops of rain. The boy and early man were now the same. Meanwhile, downriver, men from Loren’s world were busy elaborating plans that would deliver Tuti, so close to the Stone Age that his brain contained almost no abstract imprints, to the world of machinery and televised news, soft drinks and government welfare.

3 comments on “ Close Encounters of the Theatrical Kind ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

How fascinating!

Insightful review Sarah!

Thanks, Julie! Great to have your company for this show.