Putting Photography in Context: An interview with Mark Alice Durant

Mark Alice Durant writes beautifully about photography. Photographs are “skins of light…the ghosts of our ancestors,” he writes, but while photography “pilfers luminescence,” it is “handcuffed to time.” Taking a photograph is “a kind of paradoxical act of prayer, a gesture toward the sanctity of the everyday that requires a temporary severing of that connection.”

Mark Alice Durant writes beautifully about photography. Photographs are “skins of light…the ghosts of our ancestors,” he writes, but while photography “pilfers luminescence,” it is “handcuffed to time.” Taking a photograph is “a kind of paradoxical act of prayer, a gesture toward the sanctity of the everyday that requires a temporary severing of that connection.”

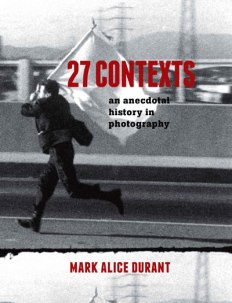

These words come from Durant’s new, hard-to-categorize book, 27 Contexts: An Anecdotal History in Photography . Neither memoir nor academic-style essay collection, it blends the two in an ambitious melding of personal and photographic history. Durant covers a dizzying range of topics, from his infatuations with photographer Josef Koudelka and filmmaker Maya Deren, to postmortem and paranormal photography, to his parents’ wedding album. Throughout, he keeps the tone accessible and doesn’t hesitate to laugh at himself—as in the chapter ‘Mary Karr is Not My Girlfriend,’ a hilarious account of his attempt to use photographs as a tool of seduction.

Durant Reading Mary Karr’s The Liar’s Club

Before becoming a writer, Durant was himself a photographer and performance artist—an evolution that he charts in the book. In 1999, though, while doing a residency at an artists’ colony, he “had this very distinct feeling that I didn’t have any images inside me any more.” He did, however, have words. Lots of them, it turned out.

In 2011, Durant founded

Saint Lucy

,

a website devoted to writing about photography and fine art. In addition to Durant’s writings, Saint Lucy features portfolios, conversations with artists and curators, and the column

One Picture/One Paragraph

, in which contributors share a photograph and write a paragraph about it.

In 2011, Durant founded

Saint Lucy

,

a website devoted to writing about photography and fine art. In addition to Durant’s writings, Saint Lucy features portfolios, conversations with artists and curators, and the column

One Picture/One Paragraph

, in which contributors share a photograph and write a paragraph about it.

This year, Saint Lucy’s projects expanded to include a publishing imprint, Saint Lucy Books. The first two titles to come off the presses were Durant’s 27 Contexts and Laura Larson’s Hidden Mother , a fascinating account of Larson’s experience adopting an Ethiopian girl blended with the history of Victorian ‘hidden mother’ photographs. (n.b. The Literate Lens will be covering this book at a later date.)

Recently, The Literate Lens connected with Durant to discuss writing about photography, researching Maya Deren, and the mystery inherent in every photograph.

Durant’s mother on her wedding day

You begin your book with an essay about your parents’ wedding album, and the discrepancy between their glamorous wedding images and the gritty reality of your life with them. Many of us have those romanticized wedding photographs burned into our memories, whether from our own weddings, our parents’, or celebrities. What do you think that does to us on a psychological level?

Well, I was trying to write that essay from the perspective of that boy, trying to describe a certain break, a moment of alienation or separation from one’s context, that time when one starts to realize one’s own personal truth. I think everyone has those moments, but maybe they’re especially common in people who become artists and, to an extent, outsiders in their own family. For me, that was the beginning of looking to photographs as a way of thinking about artifice and performance, and the discrepancy between the reality I observed and the performance of photographs themselves.

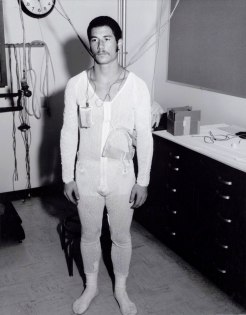

You studied with the photographer Larry Sultan in San Francisco. It seems that the biggest lesson you learned from him, through his projects Evidence and Pictures From Home , was about the mystery inherent in every photograph.

Untitled, Evidence/ 1977

That’s right. I am grateful that I met Larry Sultan. He taught me so much about photography and about being an artist. When I met him he had recently collaborated with Mike Mandel on the project Evidence , [using images from government archives such as NASA and the Jet Propulsion Lab]. The project is an ironic presentation of the inherent uncanny-ness of photographs. Those images point at something, they’re denotative, but what they actually mean is often inscrutable. So Evidence proves the point that photographs are contingent on context for their meaning. It’s interesting that there is now a surging interest in vernacular photographs – collections of snapshots of people in their swimming pools or taking a walk, the surrealism of the everyday. Within every photograph, there is evidence of specificity and a bigger question of meaning.

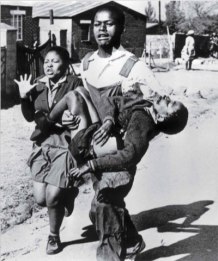

Despite the ambiguity of photographs, there are some documentary images that become iconic for the way they symbolize suffering, heroism or both. You write about the epiphany you experienced when you saw Sam Nzima’s photograph of three students fleeing during the 1976 Soweto Uprising. Given the welter of imagery we’re subjected to these days, do you think young people are having that same experience of having a single still image be a turning point in their lives?

Soweto Uprising , (c) Sam Nzima, 1976

I think so. I teach, so I broach some of these subjects with my students. I know many young people who are sensitive and angry, more than I was at their age. There is a level of political sophistication, activism and media savvy among young people that gives me tremendous hope. I think the argument about whether photography de-sensitizes us is a tired idea. It is certainly a point of philosophical discussion, but more importantly, what are young people doing? In the case of the Freddie Gray uprising here in Baltimore two years ago, compared to the established news media, it was young people who were making the most challenging and informed images.

In your chapter about the avant-garde filmmaker Maya Deren, you fantasize about entering a photograph of her on the beach. Is that a common fantasy of yours, and if so, what other photographs have you wanted to enter?

Maya Deren

[Laughs] Well, I think that I try to animate images through a kind of conscious engagement with them, it’s one of the things I do as an artist, a viewer and a writer. I was researching a book on Deren and I spent a lot of time in the Maya Deren archives in New York and Boston. There’s a kind of quiet, contemplative bubble you become immersed in when you’re in those environments—you’re in this intense study of personal papers, it’s strangely formal, and yet intimate at the same time. There’s a sense of being pulled in, piercing, passing through some kind of membrane.

I love that answer. I think it applies to all photography, in some way—that’s why photographs are so powerful. But you dodged the question; let me ask it in a different way. Is there a photo you’d like to inhabit permanently? Or at least vacation in from time to time?

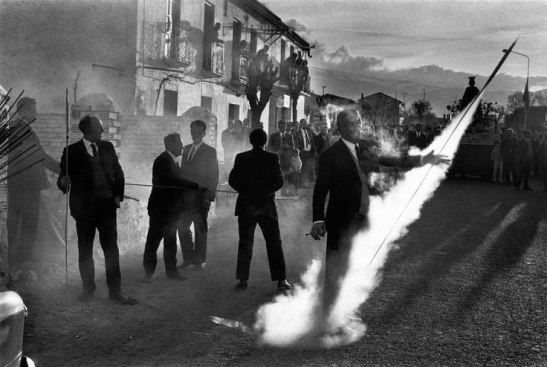

It’s difficult to choose one, so let me choose two. The first would be Andre Kertesz’s image Meudon 1928 which shows a man walking down the street carrying a package wrapped in newspaper under his arm, behind him other people are walking and in the distance a locomotive train, with smoke billowing from its stack, is barreling over an impossibly high stone bridge. That image is such a mystery to me, more inherently surreal than any canvas by Dali or Magritte. The second is an image by Josef Koudelka taken in Spain at a carnival or religious holiday. Men in suits are lighting fireworks and sending them skyward. There is something magical about how the late afternoon light suffuses the entire scene, I could live in the ecstasy of that moment.

Guadix, Grenada, Andalucía, Spain, 1971, (c) Josef Koudelka

Something I like about your writing is that you discuss ‘deep’ ideas, but it is very accessible. There’s none of the pretension that one often encounters in more academic writing about art. Another thing I like is your eclectic tastes: you choose subjects other people probably wouldn’t, like paranormal photography.

Well, I am a ridiculous person. I have my obsessions with the otherworldly — spirit photographs, ectoplasm, the ‘thougtographs’ of Ted Serios, and UFO’s. But I’m also deeply moved by art and artists and can get into strange fantasy spaces, as in the case of my obsessions with Maya Deren and Mary Karr. I think if one is going to have a critical relationship to culture you also have to make fun of yourself. As someone from a working-class background, I find the pretensions of some of the art world absurd. My whole approach to writing and teaching is to be as accessible as possible. I don’t believe you have to be obscure to deal with complex issues. I feel like accessibility, enthusiasm and curiosity are my lifeblood, the things that have created a path for me.

I’m interested, because I also have a background as a practicing artist (though not as extensive as yours): do you think being an artist/photographer has made you approach writing differently?

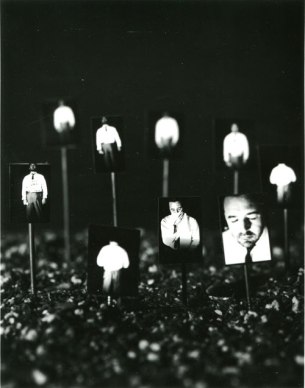

Internal Landscape, Mark Alice Durant, 1994

I am not a critic; I am not an art historian or a scholar of any sort. I am an artist who writes. I am not sure if that is good or bad, it just means that I write about art, and photography in particular, from the inside. While my lack of scholarly pedigree might be, in some cases, a limitation, I also think it allows a kind of freedom, perhaps a naïve freedom, but nonetheless, I have no theoretical or critical agenda. I can follow my instincts, curiosities and obsessions without having to justify myself.

How has it been for you to share your work through Saint Lucy? Have you built a community up around the site?

I started Saint Lucy in 2011 for a number of reasons. I wanted to have an online archive of some of the things I had written that were published in somewhat obscure journals, and also a venue to publish articles that I pitched to editors but which were not commissioned. Since then, Saint Lucy has kind of taken over my life, in a good way mostly. In addition to my essays there are conversations with artists and writers. This is one of my favorite things that has happened – I’ve had wide-ranging conversations with dozens of people I admire, such as Zoe Leonard, Paul Chan, David Maisel, Pieter Hugo, and Elinor Carucci, to name a few. Saint Lucy also has a feature called ‘The Sevens’ which features selections of works of artists I am interested in. The site gets a lot of visits; many teachers use it as a resource, which makes me very happy.

I really like the column One Picture, One Paragraph (on Saint Lucy) where contributors share a photograph and write a paragraph about it. How did that get started?

“I wasn’t sure if they were husband and wife. I wasn’t sure if they were neighbors. I wasn’t sure if they even knew each other.” From Josh Sinn’s One Picture/One Paragraph on saint-lucy.com

It comes from an assignment I used to give to my students. I would hand out photos and make them write a paragraph about the image —this was to help them overcome the fear of writing and to illustrate just how malleable photographic meaning is. I wanted Saint Lucy to have a place where people could contribute, so it was more than just my own writing. Photography is relatively democratic, most people have been raised in an image-rich environment, they have made images, been photographed. I realized I could ask just about anyone to contribute to One Picture/One Paragraph, they didn’t have to be artists. I could ask my mom, or my neighbor. It was a way of opening the site up. I don’t give any directions—people choose any image at all, it could be a childhood snapshot, an image they made or found. They write whatever they want, in any style or approach. I post whatever comes in, whether it’s a literal description, the story of how the image was made, or a poetic response to it.

What’s your next project? Is there a subject or photographer you’re itching to write about?

I have a long list of essay ideas. I am currently working on something titled ‘My Brief Friendship with Richard Avedon’ which is a reappraisal of his work while also being a humorous account of my attempt to befriend him. I have been thinking a lot about photographic portraiture lately. It is such a basic photographic act — one person points a camera another person — so simple yet so complex and varied. The working title is ‘Some People Appear Before the Camera.’ I’m not a scholar, so it wouldn’t be a theoretical approach. In the end, what I have to offer is something that’s informed but personal. I’ve spent my life thinking about photographs, and I hope to write some lively sentences to share my enthusiasms with others.

4 comments on “ Putting Photography in Context: An interview with Mark Alice Durant ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

One Picture/One Paragraph is such a thoughtful idea. I plan to try it with my son – thanks!

Hi Sarah,

It was great to see you again last week at the farmers market and we hope to see you again tomorrow morning.

Thanks for this great interview with Mark. I have met him a few times via CCNY and it’s very interesting to get into his head through your questions.

All the best and have a great night,

Saul

Saul Robbins

saul@saulrobbins.com http://www.saulrobbins.com

Facebook: SaulRobbins Linkedin: Saul Robbins Instagram: Saul.Robbins Skype: SaulRobbins

>

Thank you, Saul! I’m out of town at the moment so no farmers market, but that is my local market now so I expect we will have many more encounters!

Thank you for another fine piece and for the introduction to this writer. (The magical, haunting Koudelka image, by the way, is one of my favorites by him or anyone.)