Unpretentious: Elsa Dorfman’s sunny photography

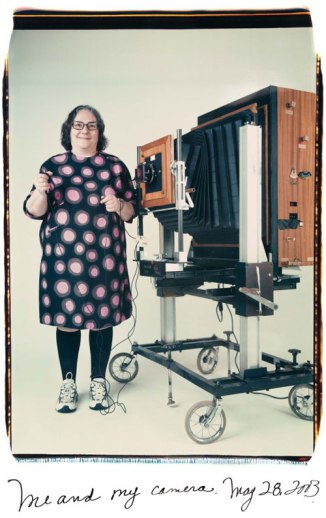

Photograph (c) Elsa Dorfman, 2003

Elsa Dorfman is not your average portrait photographer. For one thing, since 1980 she has worked exclusively on an enormous Polaroid 20×24 camera, one of only five such machines that the company made. For another, she likes to make portraits of people looking happy, not serious. “Life is hard enough, when you’re down you don’t need to walk around with a picture of it,” she says.

Her work is what her friend, the great documentary filmmaker Errol Morris , described as “a perfect combination of Renaissance portraiture and dime store photography,” in a letter of support he wrote for her application for a Guggenheim Fellowship. Dorfman didn’t get that fellowship, but now she has something arguably better: Morris has made a film about her.

The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography is a film as unpretentious and charming as its subject. It’s an unexpected move from Morris, who has made a career of exploring political and ethical morasses. But, as you’d expect from the director of The Thin Blue Line and The Fog of War , its attention to detail is exquisite and revealing.

Young Elsa Dorfman. Photograph (c) Elsa Dorfman

Born in 1937, Dorfman describes herself as “one lucky little Jewish girl who escaped by the skin of her teeth.” That escape (presumably from suburbia and tradition) first landed her at the offices of Grove Press in New York in the 1950s, when a ragtag army of Beat poets and writers was passing through the office. One day, a scruffy young man asked, “Where’s the can?” and the fact that she didn’t know the euphemism for toilet made him laugh. They became fast friends. His name was Allen Ginsberg.

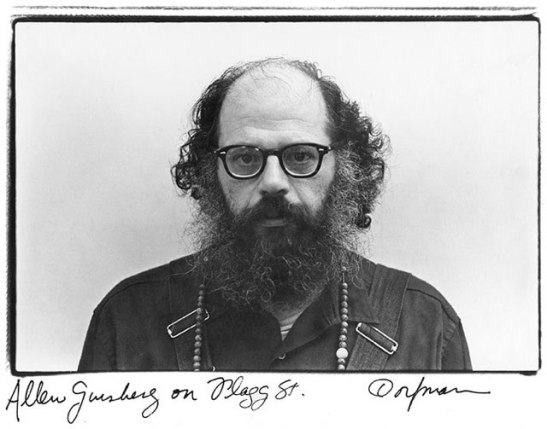

Dorfman photographed Ginsberg throughout his life, and says it was impossible to make a bad picture of him: “Allen really understood a camera. He could disarm himself, so he wouldn’t be guarded.” She also credits Ginsberg’s raw, direct poetry with influencing what she calls her “literary” style of photography, in which “what you are is ok, you don’t have to be cosmeticized.”

Allen Ginsberg. Photograph (c) Elsa Dorfman

When the pressure of life in New York started to get to her, she moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where her house became a stopping-off point for Beat artists and writers. Her candid photos of them became her first book, Elsa’s Housebook: A Woman’s Photojournal . Mostly, though, Dorfman did not behave like an aspiring artist-photographer. She made “sunny” work, and sold her prints for $2 apiece out of a shopping cart in Harvard Square.

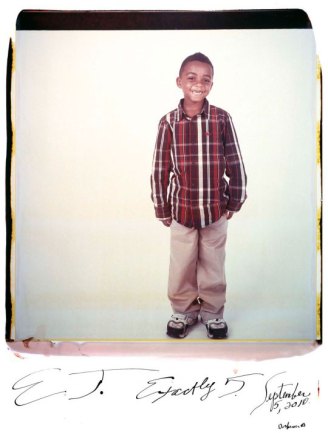

Photograph (c) Elsa Dorfman, 2010

Dorfman doesn’t make any grand claims for photography. In a clip from an early interview, she is asked if the camera tells the truth. “Absolutely not!” she replies emphatically. The best a photograph can do is try to “nail down the now,” she says, even though “the now is racing beyond you.”

Despite this—or perhaps because of it—from 1980 onwards Dorfman chose to work exclusively with the Polaroid 20×24 camera, a slow and cumbersome machine whose prints were so expensive that, for each sitter, she took only two shots. From these she allowed the client to chose one, while she kept the other, calling it “the B-side.”

As Dorfman and Morris (her neighbor in Cambridge) look through these B-sides, the film becomes a meditation on mortality. After years in storage, some of the large Polaroids have cracked and faded, becoming what Morris calls “fugitive images.” Polaroid has gone out of business, and at eighty, Dorfman has decided to retire. What remains from this lifetime of looking? We get a hint when Dorfman pulls out a lifesize print of Ginsberg, and Morris asks, “Does looking at this bring Allen back?” “Yes,” Dorfman replies, her face at once pained, wistful and glad.

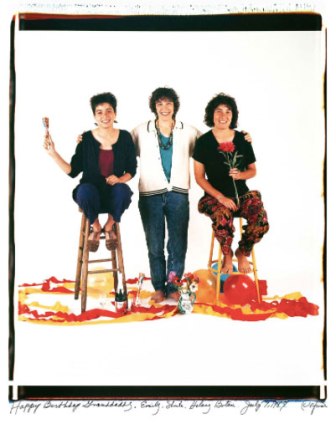

The Boteins, Photograph (c) Elsa Dorfman, 1987

Other images, made for commercial clients, are fun and cheeky—“I do whip up a certain energy,” she admits. Their lightness runs counter to the trend of “serious” art portraiture— I’ve written before about the trend of dour and blank portraits—and perhaps because of that, Dorfman was not embraced by the establishment. “I was never a pet [at Polaroid],” she says.

The B-Side opens theatrically on June 30. The screening I attended, part of the Stranger Than Fiction documentary series at the IFC Center, featured a Q&A with Dorfman and Morris after the film, and it was a pleasure to see the two friends interact. “I think people who see the film realize how adorable Elsa is,” Morris said, which is true—but if anything, she was even more adorable in the flesh.

Asked if the 20×24 format made her photographs special, Dorfman mused that it was “a miracle that the 20×24 came out when it did,” creating “a window for people like me.” The size and expense of making a print encouraged deep concentration and thoughtfulness, whereas, “Now, people don’t even make prints.”

Dorfman and Morris at the IFC Center. Photograph (c) Sarah Coleman

Otherwise, though, the “one lucky little Jewish girl” refused to be grandiose or immodest. When Morris first proposed making a film, she said, “I didn’t see a movie.” Of the recognition she has received since the movie came out, she remarked drily, “Well, I’ve heard from a lot of people from elementary school!”

If there’s any justice, Dorfman’s charming and unpretentious portraiture should be getting a lot more recognition soon.

The B-Side trailer:

One comment on “ Unpretentious: Elsa Dorfman’s sunny photography ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Wow! This is a wonderful post. I’ve had your blog in my “read when you get a chance” links for months (maybe years), and today’s the day I got to it. I don’t know why. It is sad it took me so long to discover you. Your site is more than extraordinary. Thank you.