Future Shock: Google Glass and Photography

Remember those Harry Potter movies where photographs in the newspaper move? Or the face recognition Arnold Schwarzenegger employed in the Terminator films? According to one industry expert, these advances are no longer outrageously far-fetched. In fact, we may not be too far away from seeing them in everyday life.

Remember those Harry Potter movies where photographs in the newspaper move? Or the face recognition Arnold Schwarzenegger employed in the Terminator films? According to one industry expert, these advances are no longer outrageously far-fetched. In fact, we may not be too far away from seeing them in everyday life.

On a recent visit to California, I got to hear Marc Levoy , a Stanford academic and computational photography specialist, make a presentation called What Google Glass Means for the Future of Photography . Levoy should know: last year he took a leave of absence from Stanford to help Google develop Project Glass . In his opinion, “it turns out that photography is one of the killer apps on Google Glass.”

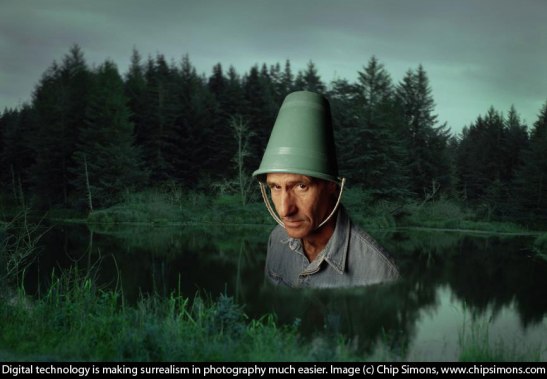

Of course, digital technology has already revolutionized photography. In under three decades, we’ve seen everything from a new surrealism in art photography to manipulated news photographs to the Presidential selfie . We’ve shared and Tweeted, and applied really cool filters to our images.

But this is just the beginning. In Levoy’s view (explained partially in this article ), with the possible exception of photojournalism, “straight” photography is about to become a relic of the past. Instead, “everything will be an amalgam, an interpretation, an enhancement, or a variation—either by the photographer as auteur or by the camera itself—under manual control or fully automatically.”

Let’s hit the pause button here. We need to distinguish between computational photography (which is being rapidly incorporated into digital cameras and cellphones) and the unique features of Google Glass (which is currently in beta testing).

In computational photography, the image the sensor gathers is considered intermediate data, and a final image is created using computation. This can happen through various means, from compositing multiple images to manipulating the illumination or focal point. Features like this will be coming soon to a camera near you.

In computational photography, the image the sensor gathers is considered intermediate data, and a final image is created using computation. This can happen through various means, from compositing multiple images to manipulating the illumination or focal point. Features like this will be coming soon to a camera near you.

Already, features like burst mode are being used in consumer cameras to capture and composite sequences of rapid-fire shots of the same subject, a bit like Harold Edgerton’s classic strobe photographs of people and objects in motion. This can be used to good effect to depict athletes in action—though in his presentation, Levoy also showed some rather creepy animated snapshots of people (similar to the moving photos in the Harry Potter films), and some “cinemagraphs”—photographs where a single element (a tress of hair, for example) was animated within an otherwise static image.

In future, Levoy said, such features will be enhanced and will lead to “superhero photography” where the output of digital cameras will far exceed human vision. We’ll be able to take clear shots at midnight, observe the minute color change effects of a pulse on a face, and magnify motion to create visual effects.

So what does Google Glass (which is basically a head-mounted cellphone) bring to the party? Only a few things, really, but they could be key to producing a new kind of hyper-subjective photography.

The first is point-of-view shooting: since Glass is hands-free, users can capture the experience of being in their body, as in this image below of a child being swung around. This feature could also be used for “eye swapping” during a videoconference, where you and your communication partner will see from each other’s perspectives.

The second is immediacy. With Glass, there will be no more fumbling for the cellphone in your pocket or the camera in your bag. Instead, taking a photograph could be as easy as blinking or saying “take a photo,” and every moment will be ripe for documentation. Nothing will be missed. If you think social media is already flooding us with banal images of people’s dogs, dinners, and dogs’ dinners, watch out. You may not want to be around for the next decade.

A third, intriguing possibility Levoy suggested was that Google Glass could increase personal safety. Wearing the device, women walking alone in dangerous neighborhoods could feel safer, since they could use Glass to record any threatening encounter. Interestingly, this may prove counter-productive: a woman wearing Google Glass was recently attacked in San Francisco precisely

because

she was wearing the device

. She did, however, turn her specs in to police, who are examining them for evidence.

A third, intriguing possibility Levoy suggested was that Google Glass could increase personal safety. Wearing the device, women walking alone in dangerous neighborhoods could feel safer, since they could use Glass to record any threatening encounter. Interestingly, this may prove counter-productive: a woman wearing Google Glass was recently attacked in San Francisco precisely

because

she was wearing the device

. She did, however, turn her specs in to police, who are examining them for evidence.

I’ve written in the past about the possibility of “deletive reality”—a futuristic and worrying use of devices like Google Glass that Levoy did not touch on in his talk (and which is spoofed brilliantly here , in British newspaper The Guardian ). Obviously, as with any technology, Google Glass can be leveraged for good or for evil. The people who attacked the Glass-wearing San Francisco woman were offended she was recording them, which is understandable: we already have way too much government surveillance without recreating the Stasi (with video). Levoy mentioned that the number one question he gets when he’s wearing his headset is, “Are you recording me?”

Although we’re probably a ways off from devices like Glass incorporating face recognition software—so that you can walk into a party and find out whether that cool-looking dude in the corner is a sociopath—it is without doubt coming. Advertisers, corporations and the FBI are

already experimenting with face recognition

to advance their causes. And if you think all this is creepy and intrusive—well, Levoy reminded the audience that privacy concerns were raised with early cellphone cameras, and ventured that anonymity is a quaint, 20th century idea we’ll all have to get over (though he drew a distinction between anonymity and privacy).

Although we’re probably a ways off from devices like Glass incorporating face recognition software—so that you can walk into a party and find out whether that cool-looking dude in the corner is a sociopath—it is without doubt coming. Advertisers, corporations and the FBI are

already experimenting with face recognition

to advance their causes. And if you think all this is creepy and intrusive—well, Levoy reminded the audience that privacy concerns were raised with early cellphone cameras, and ventured that anonymity is a quaint, 20th century idea we’ll all have to get over (though he drew a distinction between anonymity and privacy).

Other applications are more positive. Watch the heartwarming video below, which shows how a paralyzed woman was able to join a camping expedition with the help of Google Glass. Levoy also mentioned the possibility of instantaneous language translation, and showed some pretty cool shots of foreign language signs morphing into English. Apparently, the beta version of Google Glass is doing this already, and it seems exciting (though not strictly related to photography). Imagine going to any country in the world and instantly being able to interpret signs and communicate with people. The implications for global understanding are huge.

For professional photographers, the picture seems a bit less rosy. Since computational cameras—Google Glass included—will enable almost anyone to take a really good photograph, they will continue to shrink the distance between amateurs and professionals. This makes me sad for my photographer friends, who have spent years learning technical and visual skills that any monkey might soon be able to accomplish. Framed your image badly? Got the focal point wrong? No worries: a push of a button will turn it into a great shot in no time.

Interestingly, I don’t think there’s an analog for this in writing, where technology hasn’t advanced much beyond word processing. Yes, we’ve seen business models in publishing change, e-readers take off, and the market being flooded with self-published books. We’ve seen the likes of E.L. James become gazillionaires by pumping out witless pornography. But as of yet, there isn’t a way for E.L. James to become James Joyce. Malcolm Gladwell’s assertion in Outliers: The Story of Success , that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to achieve mastery in a discipline, is still true for writing.

I’m sure a lot of pro photographers will argue this point, saying there are levels of artistry in photography that an algorithm will never recreate. I hope you’re right. I think you are, actually—because as much as camera technology might advance, it won’t give us all great eyes. Let’s not forget that when digital books first came along, there was a lot of noise about interactivity and crowd-sourcing of stories. That hasn’t come to fruition, because people still like to be told a well-crafted story by a singular voice. Vision, selection and creative expression still count. I think/hope/pray they’ll continue to do so, however many bits and bytes we add to the equation.

2 comments on “ Future Shock: Google Glass and Photography ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Great post, Sarah! Should be interesting to see where and how Google Glass is used 10 years from now.

A good read that leaves me thinking on several levels.