The Birth of Arbus

There are artists whose work is so raw, so emotionally direct, that it seems potentially dangerous. In 1938, the Surrealist artist André Breton described Frida Kahlo’s painting as “a ribbon around a bomb.” In a similar vein, after sitting for a portrait with Diane Arbus in 1963, Norman Mailer remarked that, “giving a camera to Diane is like putting a live grenade in the hands of a child.”

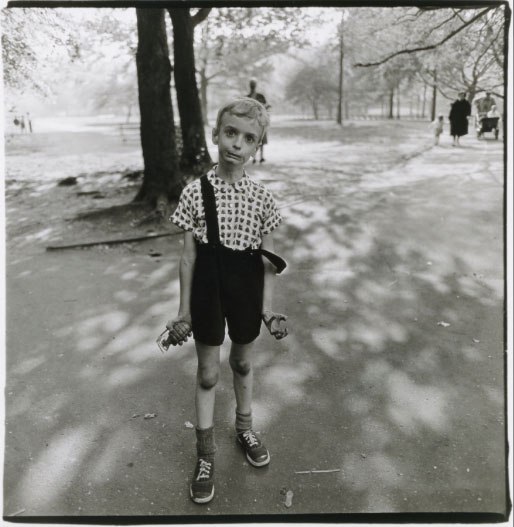

Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, NYC , 1962, by Diane Arbus

No doubt, Breton and Mailer were responding to the open and unguarded qualities both women brought their work—the lack of filter, as if they had opened a vein and poured themselves out, in all their need and power and carnality. (One can see why that was terrifying to a sexist like Mailer.) Of course, their subjects were different: Kahlo mostly painted herself, while Arbus gravitated toward transvestites, midgets, and others on the margins of society. But Arbus felt an intense affinity for her subjects, who affirmed her own sense of misfit-dom. In this way, her images are self-portraiture of a sort.

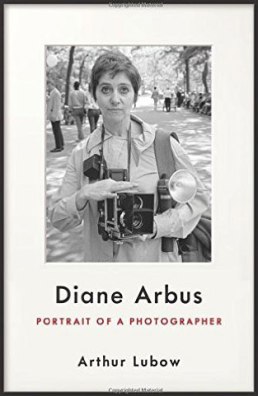

Where did Arbus’s insatiability, her emotional directness and attraction to marginal characters come from? We’re often told that art should stand on its own, and Arbus’s does, but at the same time, her portraits are so psychologically acute, and so intertwined with her own trajectory, that it’s fascinating to examine both in tandem. A

big new biography

by Arthur Lubow, coinciding with the Met Breuer’s just-opened

diane arbus: in the beginning

, offer an opportunity to do just that.

Where did Arbus’s insatiability, her emotional directness and attraction to marginal characters come from? We’re often told that art should stand on its own, and Arbus’s does, but at the same time, her portraits are so psychologically acute, and so intertwined with her own trajectory, that it’s fascinating to examine both in tandem. A

big new biography

by Arthur Lubow, coinciding with the Met Breuer’s just-opened

diane arbus: in the beginning

, offer an opportunity to do just that.

Lubow’s biography runs long at 776 pages, but reads easily, cut up into short chapters with zingy titles like ‘A Spanish Impasse’ and ‘And Then You’re a Nudist.’ He paints a picture of young Diane as an odd duck, embarrassed by her family’s wealth and always strikingly original. Tellingly, she was drawn to flawed things: as a student at the Fieldston School, if given two cups to paint,“she would portray the shiny new one with mechanical proficiency, while the blemished, imperfect cup she regarded and represented passionately.” Alienated from their parents, she and her older brother Howard formed a fellowship of two that extended to a sexual relationship: Lubow drops the bombshell that it may have continued up to her death. (It makes sense that someone who had a fuzzy sense of boundaries would have sought out, as her subjects, people who routinely crossed them.)

Untitled, 1970-71, by Diane Arbus, was taken shortly before her suicide

The Met Breuer’s show traces Arbus’s artistic beginnings. Taken from the museum’s huge archive donated by daughters Doon and Amy, the show covers the period 1956 to 1962, showing material never exhibited before. 1956 is also the year Lubow begins his account of Arbus, calling it (in a cute nod to photo enthusiasts) ‘The Decisive Moment.’ Previously, Diane had played second fiddle to her husband Allan, but in 1956 she announced that she was leaving their joint fashion photography studio, whose world she found stultifying and fake. It was the year she started going out on the streets, looking for secrets to uncover.

Photograph by Sarah Coleman

I loved the way the show represents this period, displaying the images on flat columns with a single photograph on the front and the back. Viewers weave through the columns, free to choose their own path. Not only does this give each image room to breathe, it emphasizes the singularity of Arbus’s vision and her magpie-like acquisitiveness. It encourages the viewer to engage with each image as intimately as Arbus engaged with her subjects. Finally, it integrates and implicates viewers, who become mingled with the images. The world depicted here may be strange and a little sordid, the display seems to say, but you’re part of it too.

Arbus’s style and technique in those early years was varied–but from the beginning, her preoccupations were in place. She had very little time for conventional beauty, preferring the odd, the flawed and the lonely. A disemboweled corpse, an old woman dying in hospital, a screenshot of a man about to be choked: some of her subjects are deeply macabre. Others offer sly social commentary, like the picture of a debutante who, though dancing, looks like a marble statue. Still others are humorous, such as the portrait of a couple where the man, smaller and cheeky-looking, is biting the woman’s ample breast through her clothes.

Lady on a bus, NYC , 1957, by Diane Arbus

These years show Arbus turning from a shy street photographer who skulked in the shadows to a confident artist who engaged intimately with her subjects. (As curator Jeff Rosenheim points out, this quality is what separated her from contemporaries like Friedlander, Winogrand and Frank, who were more likely to grab an image on the fly.) Engagement wasn’t all she demanded: her subjects had to drop any pretense and be emotionally naked. When she began photographing midgets, Lubow recounts, she remarked that “they were as amazing-looking as movie stars, and yet, unlike celebrities, they had not been photographed incessantly until a coating of defensive shellac masked them.”

It’s interesting to read, in Lubow’s biography, about the circumstances behind some of these images–like the famous portrait Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, NYC , shot in 1962 (shown at the top of this page). That image has been criticized as being cruel or unrepresentative, an awkward shot pulled from a contact sheet of images where the same boy is smiling . But Colin Wood, the subject of the photo, reveals in an interview with Lubow that Arbus perfectly captured his anger at his divorcing parents’ neglect. “She saw in me the frustration, the anger at my surroundings, the kid waiting to explode but can’t because he’s constrained by his background,” he told Lubow.

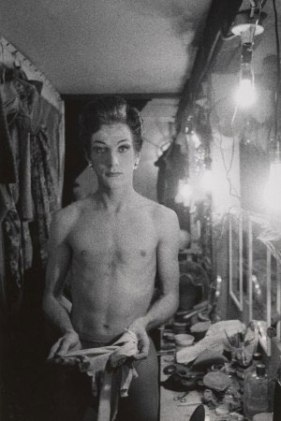

Female impersonator holding long gloves, Hempstead, L.I. , 1959, by Diane Arbus

Arbus could be relentless. When a tattoo-covered man known as Jack Dracula turned her request for a portrait down, she pursued him up to New London, Connecticut and badgered him into posing. She was charming but manipulative, fragile but persistent. Both book and exhibition reveal the young artist as an insatiable seeker, someone who kept her childlike sense of wonder and used it to interrogate the world, one frame at a time. Nothing was enough; there was always more to uncover. “I want to photograph everybody,” she once told an art director.

At the heart of all this seeking was the depression, an emptiness that could never quite be filled. Evsa Model, the husband of her mentor Lisette Model, “believed that Diane drank up energy from Lisette like a vampire, and he disapproved when his wife spent too much time with her and returned home exhausted,” Lubow writes. But if Diane consumed people, she also revealed to them her own emotional fragility. Ultimately, it’s that fragility that makes even her most controversial pictures so delicate, affecting and timeless.

One comment on “ The Birth of Arbus ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

A very enjoyable, enlightening and easy read, a great intro to a fascinating photographer. Plus, the photo and description of the show space was a treat.