Georgia O’Keeffe, Modernism and Photography

This is the first of two posts from London, U.K.

Of all the notable 20 th century artists, Georgia O’Keeffe might win the prize for Most Featured on Posters and Paraphenalia. It’s easy to see why. Her cropped, close-up paintings of flowers—the work for which she’s most known—have a pared-down, decorative quality and colorfulness that look good on walls. Owning one signifies that you like art, up to a point—but maybe not so much that you’d want to discuss Fauvism or the latest Lars von Trier film.

I have to admit that, for years, I’ve tended to dismiss O’Keeffe, mostly on the basis of those flower paintings, which—showing up as they do on a gazillion tea towels and mugs—have come to seem middlebrow and banal. Having researched this period, I also know that O’Keeffe’s rise to fame was orchestrated by the influential photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, who was madly in love with her. Though the feminist in me always wanted to see her as a great artist, the cynic wondered if Stieglitz would have championed her work if she’d been older and less attractive.

A fascinating exhibition at London’s Tate Modern wants to set me straight, however. The show, which is simply called Georgia O’Keeffe , is a broad retrospective that aims to rescue O’Keeffe from the giddy scent of flowers, and show her instead as a passionate, inventive painter of many subjects. It argues for her as a major Modernist, and shows that she drew inspiration from sources that included music, photography and the American landscape.

One of the ways it does this is to draw connections between O’Keeffe and various photographers, from her husband Alfred Stieglitz to her close friend Ansel Adams. O’Keeffe met Stieglitz in 1916, when she was a struggling twenty-eight year old Texan artist/schoolteacher, and he was a married fifty-one year old. He was, at the time, the most powerful man in the New York art world, having brought European Modernist artists like Picasso, Rodin and Brancusi to New York. He was attracted to O’Keeffe’s boldness on paper, and drawn to her as a woman too. Within two years, he had paid for her to move to New York and set up a studio.

As a young artist, O’Keeffe was fascinated by the way photographers were beginning to see the world in new, radical ways. Seeking to break molds herself, she drew on photography’s capacity for minimalism, at first influenced by Stieglitz’s use of snow and smoke to form large fields of white.

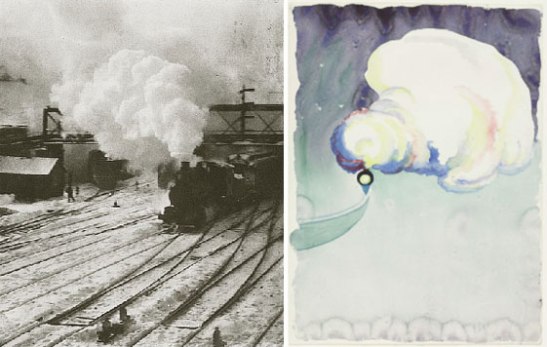

In the New York Central Yards , 1903, by Alfred Stieglitz (L); Train at Night in the Desert , 1916, by Georgia O’Keeffe

Looking at O’Keeffe’s 1916 watercolor Train at Night in the Desert next to Stieglitz’s 1903 Snapshot—In the New York Central Yards , the influence is clear—and it’s easy to see how the fifty-year-old Stieglitz might have been flattered by the imitative attentions of this eager younger woman. But it’s also clear that O’Keeffe was trying to stake out new ground for painting, and to bring a particular kind of soulfulness to Modernism. She had read Wassily Kandinsky’s book The Art of Spiritual Harmony , and believed in synesthesia, and the correspondence of color and sound especially. Her 1919 painting Red and Orange Streak was an attempt to visually convey an aural experience of the West Texas plains, with cows lowing plaintively for calves in the night. Other paintings evoked music, drawing on her background as an accomplished violinist.

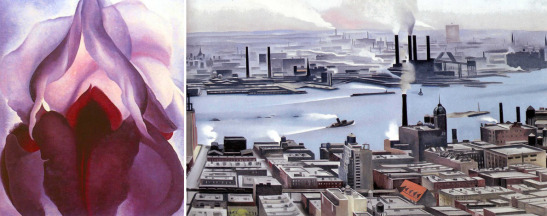

Years later, when she and Stieglitz were married and living on the thirtieth floor of the Shelton Hotel in midtown Manhattan, both were inspired by the views from their windows. At times, they depicted the same subject: O’Keeffe’s East River from the 30 th Story of the Shelton Hotel , 1928 (shown below) could almost be a painted version of Stieglitz’s 1927 From the Shelton, New York (Room 3003) Looking Southeast . But O’Keeffe pushed her explorations of the city further than Stieglitz. While he stayed removed, observing from on high, she went into the streets, capturing the vertiginous buildings from below. Some of her paintings were detailed and others minimal, with the buildings forming shapes and lines that related to her more purely abstract work.

Really, though, it was Paul Strand whose photographs influenced her most. A protégé of Stieglitz’s, Strand had started his career by emulating his mentor’s soft-focus Pictorialist work—and then, around 1915, made a major breakthrough by using a large-format camera. This enabled him to hone in on objects, getting so close that their details turned into abstract compositions. When O’Keeffe first met Stieglitz in 1916, she was exposed to Strand’s work. The following year, she wrote that she had been “making Strand photographs for myself in my head.”

Abstraction, Bowls, Twin Lakes, Connecticut , 1916, by Paul Strand (L), Twin Calla Lilies on Pink , 1928, by Georgia O’Keeffe (R).

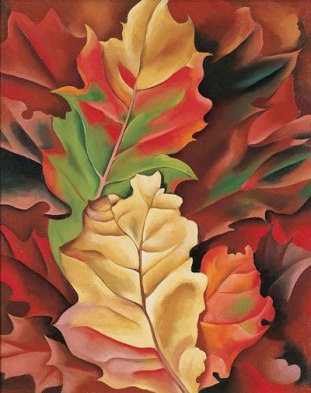

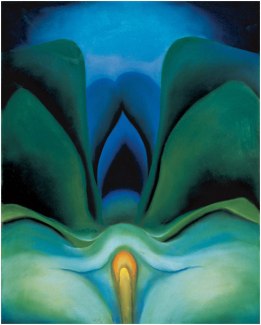

And so it was that, when she came to paint flowers, O’Keeffe chose to zoom in and crop her frame, as Strand did. “Nobody sees a flower—really—it is so small—we haven’t time—and to see takes time,” she wrote. “So I said to myself—I’ll paint what I see—what the flower is to me, but I’ll paint it big and they’ll be surprised into taking time to look at it.”

How sexual were these paintings meant to be? Stieglitz, whose nude photographs of her show that he was erotically obsessed with O’Keeffe, happily encouraged Freudian readings of her work. (In an enlightening 2009 review , Jerry Saltz writes that the sizzling nude photographs “transformed the two of them into the equivalent of an art world Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt.”)

For her part, though, O’Keeffe got tired of this angle pretty quickly. “You hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower—and I don’t,” she wrote. It might be argued that, by painting huge pistils and stamens, she was asking for it—but that is somewhat akin to saying that women who wear miniskirts want to get raped. Probably, she was more influenced by Strand’s photographs, and by her teacher Arthur Wesley Dow’s book on composition , in which he wrote that the essence of a good composition was to “fill a space in a beautiful way.”

The exhibition at the Tate Modern does a good job of teasing all this out. Whether it succeeds in establishing O’Keeffe as a leading Modernist, though, is a more vexing question. Looking at the seven decades-worth of work shown here, I felt that O’Keeffe was an original, passionate artist. But there was still the swirly, woozy feeling of some of the paintings, and their candy colors. Are these the hallmarks of a lesser artist, or do I just think so because I’ve drunk the male-art-critic Kool-Aid? That’s a chicken-and-egg question that I still can’t quite resolve.

Not just a one-trick pony: Georgia O’Keeffe painted flowers ( Flower of Life II , 1925, L) but also city scenes ( East River from the 30th Story of the Shelton Hotel , 1928, R)

Ironically, though, I did gain a new appreciation for the flower paintings. Sure, we see them as hackneyed now, but in their time, their scale—and yes, their sensuality—was groundbreaking. O’Keeffe may have been annoyed by the way they were read as sexual, but their boldness inspired a younger generation of women artists to make radical work. Take Judy Chicago’s collaborative 1970s installation The Dinner Party , which centers around flower-vulva plates, and which was directly inspired by O’Keeffe.

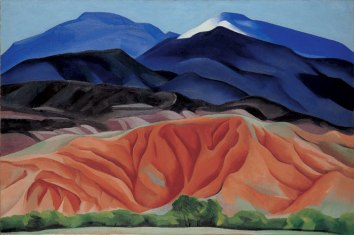

In the late 1920s, feeling suffocated by Stieglitz, her flower paintings, and New York, O’Keeffe went on a trip to New Mexico. She immediately fell in love with the landscape and felt a freedom that had eluded her in New York; she would spend much of the rest of her life there. The 2011 volume My Faraway One , which collects the copious, passionate and conflict-ridden correspondence between Stieglitz and O’Keeffe, shows her growing more assertive during this time. “I chose coming away because here at least I feel good—and it makes me feel I am growing very tall and straight inside—and very still—Maybe you will not love me for it—but for me it seems to be the best thing I can do for you,” she wrote Stieglitz in 1929.

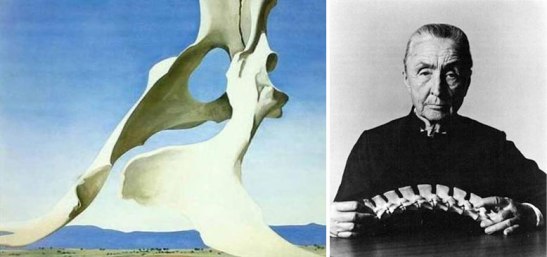

In New Mexico, O’Keeffe began collecting bones of animals that had perished in the desert due to drought. When she painted them, she sometimes brought the same cropping techniques she’d used with her flower paintings—but, being less colorful, these paintings have a more austere feel. I liked the close-ups much better than the works in which bleached skulls float over desert landscapes, which seem a bit trippy and kitsch, though Cow’s Skull: Red, White and Blue has been hailed as “a quintessential icon of the American West.”

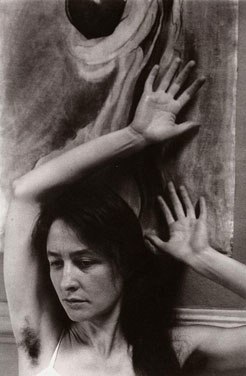

Pelvis with the Distance , 1943, by Georgia O’Keeffe (L); Portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe , photographer and date unknown, R

Through all her transitions, O’Keeffe’s passion for painting never dimmed. She would live to be 98, working up to her death, becoming almost as weathered as those desert bones herself. Her wise, wrinkled face would appear in more photographs, becoming a symbol of survival and vitality, and an icon in its own right.

Georgia O’Keeffe is on view at the Tate Modern , London, until October 30.

11 comments on “ Georgia O’Keeffe, Modernism and Photography ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Love it. Thank you Sarah. Now to get to London….

I am fascinated by both the woman and her work. You did an outstanding job on this post about Georgia O’Keefe. Thank you for doing this tremendous woman justice! ❤

Thank you so much for taking the time to comment, AmyRose. Glad you enjoyed!

You are welcome, Sarah!!! ❤

I have been an admirer of Georgia OKeeffe since you sent me to an exhibition In San Francisco, but this sounds better. I must go to Tate Modern before the exhibition closes.

Michael, it’s a nice excuse for a day out in London. She was a fascinating woman.

I have begun reading quite a bit about artists from this era.

I started with Ansel Adams, Weston and am slowly moving my way east:). Growing up with image of O’Keeffe’s work being highly sexualised. It was a surprising and refreshing discovery to find her views on the matter. She was a groundbreaking artist who (in my opinion) out grew Stieglitz.

Wonderful piece, please keep it up.

John Lee

One last point, that picture of Georgia OKeeffe taken by Ansel Adams which you have included is one of my favourites. It shows her as a human being vs an icon.

John

Agreed, John! That’s why I wanted to include it in the post. Thanks.

I’ve loved O’Keeffe since I was introduced to her in college. Thanks for the great review. Although I understand your questioning her art when it comes to commercial overuse, her work MUST be seen in person. That was the biggest surprise and enlightenment for me. Looking at her art online, in a book or heaven forbid, a napkin is definitely not the way to absorb her intent and spirit that only can be recieved by looking at the original work and seeing all the brushstrokes and the detail she put into her color choices and the painstaking blending of those hues. The scale of her work is incredible as well. Do you know if this exhibit will be coming to the United States? Please say yes:)

Thanks, Brenda! I just looked, and the only north American stop the exhibit will make is in Toronto next summer. Time for a trip to Canada perhaps?? http://bit.ly/2dpYZ2Q